The Real Dog Day Afternoon

The Real Dog Day Afternoon

And Other Accounts of Bank Robberies

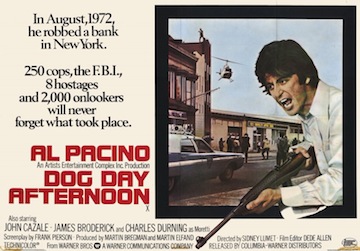

This past August 22nd was the 40th anniversary of the bank robbery that was the basis for the movie Dog Day Afternoon – a robbery of the Chase Manhattan branch at Avenue P and East Third Street in Brooklyn’s Gravesend neighborhood.

The movie was based on an account in the September 22, 1972 Life Magazine issue, written by P.F. Kluge and Thomas Moore (see pages 66-74).

Our request to Chase alumni for firsthand accounts of the robbery and ensuing hostage situation led us to discover a small error in that article and a still vivid memory by Ralph Aiello, the then rookie HR officer who tipped off corporate security that something was amiss at the branch.

Aiello, just four years into what would become a 39-year career with Chase, was an assistant treasurer and HR officer for the Bronx and Westchester divisions of the bank, working out of the “Metropolitan Banking” floor (10) at 1 CMP.

He was helping out Joe Anterio, the officer for Brooklyn and Staten Island. Both reported to Doug Randall. The Life article credits Anterio with what happened next.

“All the HR officers with branch responsibilities had individual training forces we would move from branch to branch depending on the day of the week, “ Aiello recalled. “The force consisted of commercial services clerks and tellers whom we’d send wherever there was heavy traffic.”

“That day I had to move a teller, Kathy Amore, from the Avenue P branch to the Neptune Avenue branch,” Aiello said. Amore, said Aiello, was “an absolutely beautiful young woman”.

When Aiello called Bob Barrett, manager of the Ave P branch, to request the transfer. “Barrett said to me, ‘Oh Ralph, what a lovely young lady, I’m so pleased to have the opportunity for her to work in my branch.’ I knew something was wrong from his voice and the completely stilted way he spoke. I asked him if there was a problem at the branch, and he answered, ‘Very much so and have a nice day.’”

Aiello immediately called Chase corporate security, which said they would take care of it and call the NYPD to check it out.

“I think it was a mistake,” Aiello offers. “Once the police approached the branch with

cherry pickers on, that’s when the whole fiasco started. Now the police inform us back at 1 CMP that there’s a hold-up in progress and they believe there are hostages.”

Years ago, Aiello said, HR kept duplicate pictures of all hires in their employment files. Aiello’s bosses, EVP Randall and Senior VP Lou Buglioli, told him to gather the files for all the branch employees to give them to the FBI, so they could identify who was who. Aiello took the files to the crime scene, along with HR head Bill Hinchman and

Dr. Granville Walker, Chase’s medical director at the time.

For those who don’t remember the story, two men held up the branch: John Wojtowicz (“Sonny” in the film, portrayed by Al Pacino) and 18-year-old Sal Naturile.

Wojtowicz was a Vietnam War vet who, after a failed heterosexual marriage, had “married” a man who wanted sex reassignment surgery – an operation to be funded with the proceeds of the robbery.

Wojtpwicz demanded that his lover be brought from Kings County Hospital’s psych ward, where he’d been admitted after a suicide attempt.

“Brooklyn turned this thing into a carnival atmosphere, with Geraldo Rivera and lots of media, and people selling things on the street,” recalled Aiello. “It was harrowing for the poor people taken hostage but exciting in a way, but I kept thinking 'that

could have been my wife.'”

Jim Wertheimer, then an Audit Manager in General Audit, remembers being ordered to the crime scene. “Indeed it was a late hot summer afternoon when I arrived at the branch in Brooklyn. Things were different on how hostage situations were handled 40 years ago, by the various law enforcement personnel on the scene. Instead of all neighboring blocks being cordoned off, only 30 or 40 yards on each side of the Chase storefront were blocked. The department must have been desperate for Audit Managers, since during almost 11 years in the department, I counted a teller’s cash once. Since it was already a hostage scene for a couple of hours, it was anticipated that many teller drawers were ransacked and maybe even the main branch vault.

Jim Wertheimer, then an Audit Manager in General Audit, remembers being ordered to the crime scene. “Indeed it was a late hot summer afternoon when I arrived at the branch in Brooklyn. Things were different on how hostage situations were handled 40 years ago, by the various law enforcement personnel on the scene. Instead of all neighboring blocks being cordoned off, only 30 or 40 yards on each side of the Chase storefront were blocked. The department must have been desperate for Audit Managers, since during almost 11 years in the department, I counted a teller’s cash once. Since it was already a hostage scene for a couple of hours, it was anticipated that many teller drawers were ransacked and maybe even the main branch vault.

“I could get real close to the Branch; I would show police my badge of authority, my 'Chase General Auditing ID' signed by Don Baldyga. I even got a casual salute from a policeman. It became evident that the end of the hostage siege was not near, so we were told to stay nearby. I remember going to a classic Brooklyn luncheonette on the same block as the Branch and hanging out for a couple of hours. Many of the businesses remained open and customers could come and go. Police would let customers through the police lines.

“As it got closer to nightfall, the crowds got larger. Word had gotten around the neighborhood and the hostage scene was reported on all the local TV stations dinnertime newscasts. The crowd was orderly, but the crime scene gradually became a 'Midsummer Night Melodrama' and the crowd became the audience. The crowd, oops, I mean audience would begin to cheer, clap and boo as events unfolded. It did not matter to the audience that if gunfire erupted, they could be in the direct line of fire.

“Finally, around 9 pm we were told to go home, and that ended the melodrama for me. I was glad that no Chase personnel got hurt, and I suspect life returned to normal.”

Wojtowicz had finally decideded to negotiate with the FBI to drive him, Sal and two hostages to Kennedy Airport, where a Chase corporate jet was fuelled and ready to take him away. At the airport, the FBI started shooting – killing Naturile.

Kathy Amore was one of the hostages. “She was so shell-shocked that she ended up telling the bank that she never again wanted to work in a branch. She became my personal assistant,” Aiello said.

(She also got married and became Kathy Battastoni.)

“I got to the office that day at 8 am and got home 7:30 am the next day,” he recalled. “We all remember certain days. In my nearly 40 years with the bank, that day still lives.”

After that robbery, HR started giving “what if there’s a robbery” training to tellers in the branches, and Aiello said the incident probably led to the introduction of Bandit Barriers – the fiberglass that goes in front of the tellers in certain locations so a robber can’t vault over the counter. Of course, Bandit Barriers don’t do a thing if the robber holds a gun to the bank manager’s head, as Wojtowicz did at Avenue P.

Aiello said enhanced security measures also followed an April 18, 1973 incident at a frequently robbed branch at 135th and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, where 42 hostages were taken by three robbers and a robber pistol whipped the manager, Al Parm. One of the bandits was on the FBI Top 10 Most Wanted List and was “killed outside the bank by the FBI, pistols flying”, Aiello recalled.

Aiello helped put together a training video on how to deal with bank robbers. “I’m in it wearing a silver mask – as a bad guy.”

Postscript – from David Cohen in the BensonhurstBean: “The intersection on Avenue P and East 3rd Street is now a quiet hub in the Orthodox Jewish community. It is a predominantly Syrian Jewish neighborhood bordering Gravesend. Today, the area feels calm and somewhat empty with most of the residents having gone to the shore during the summer months.

“450 Avenue P was most recently a medical center but is currently vacant. The sides of the building are covered in graffiti and the parking lot is full of weeds. Neighboring the now vacant building is a kosher sushi restaurant, a florist that is closed for the summer and a Middle Eastern grocery.”

* * *

From Ken Jablon: I had no experience with the Brooklyn robbery because I did not join the bank until 1976, but I did have experience with a hostage situation with a Chase branch in the Bronx.

In the early 1980s, I was in charge of the Chase branches in the Bronx, Westchester and mid-Hudson area. Without exaggeration, a Chase branch in the Bronx was robbed every one or two weeks. One particular branch on Zerega Avenue in the northwest Bronx was robbed three times in a few months. After the third time, the NYPD stationed an unmarked police car a few blocks from the branch with undercover police officers. A system was set up, so that if the branch was robbed again, the teller alarm would notify the police in the car.

The branch was robbed again. The police officers showed up while the robbers were still in the branch and peered into the front windows. Although the officers were in civilian clothes, they were white and almost no one in the neighborhood or the branch was. The robbers immediately knew it was the police and started a hostage situation. Luckily, it did not last very long and they gave themselves up. The branch was closed soon after.

* * *

From Charles Salmans: Before I joined Chase via Chemical Bank, I was a press spokesman with Bankers Trust, which at the time had a small retail branch in Greenwich Village.

The year was 1975, and Patty Hearst had just been captured after her own role, coerced or not, participating in a California bank robbery along with members of the Symbionese Liberation Army. And Dog Day Afternoon had just opened in movie theaters in New York.

On October 6, a young man entered the Bankers Trust branch in a copycat staging of the event portrayed in the movie. Entering the Greenwich Village branch at the 3 pm closing time, the gunman took 10 hostages, claimed to be a member of the Symbionese Liberation Army, and demanded the release of Patty Hearst and three other SLA members – Emily and William Harris and Wendy Yoshimura. He told the cops arriving on the scene that he had an accomplice, which he did not. He was equipped not only with a pistol and a shotgun but also with a list of phone numbers of the New York newspapers and radio stations, along with the phone numbers of counterculture publications such as High Times. He immediately began to call the press to discuss his demand. This became the top story on first local, then national TV and radio and the front page of the afternoon Post.

As with the Chase event in Brooklyn some three years earlier, the biggest challenge to the NYPD was crowd control, and the sympathies of a Greenwich Village crowd back then were certainly not with the establishment. In contrast to the original event, no one was hurt in the end. The gunman was alone. His connection with the SLA was a figment of his imagination. The cops sent in plenty of beer and sandwiches (perhaps laced with barbiturates) The gunman began to doze, and he was captured some eight hours after the siege began.

As Bankers Trust spokesman, I dealt with the press for the full eight hours of the siege, which was pretty stressful. Life would have been easier if I had seen the movie myself at the time. So I dealt with the event not realizing that the gunman was copying Dog Day Afternoon.

An Associated Press account of the incident can be found here.