Life After Chase: Lou Morrell

Life After Chase: Lou Morrell

Truly, for the Birds – All Birds

One can understand why New York’s City Council declared “Lou Morrell Day” on April 29, 2004. He had been a member of the board of New York’s One Stop for Coordinated Senior Services since 1990 and president of its board from October 1995 to June 2003. Chase had named him “Outstanding Volunteer” in 2000, honoring him for that work and his role as Chase’s representative on the business committee of the Wildlife Conservation Society, where he served from 1996 to 2002 .

Since then he’s given playwrights, actors and the birds of North America every reason to declare their own days in his honor.

Morrell, who began at Chemical Bank in June 1970 and left Chase in April 2006 as Managing Director, Parent Company Function Head in Finance/Corporate Treasury, brings his business-honed expertise to not-for-profits.

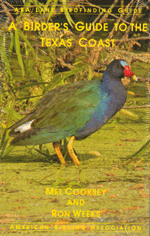

He led the Emerging Artists Theatre from June 2006 to October 2011, and has chaired the American Birding Association (ABA) since October 2010, having joined its board in June 2008. The ABA – which, Morrell points out with a laugh, owns the www.aba.org URL over the American Bar Association, the American Bankers Association and the American Bartenders Association – is the primary organization in North America representing the birding community, promoting birding skills, ornithological knowledge and the development of a conservation ethic.

Morrell said the boards sought him out, knowing of his background in finance, regulation, planning, capital and structure. “I’m invited to come because of my background in not-for-profits and turnarounds. These organizations have great missions and significant activities but have not operated as a corporation, which, in essence, they are.

“Not-for profits have come under increased regulation and review by both federal and state authorities. Moreover, once you hit budgets over $300,000, you begin to be subject to increased reporting under the IRS Form 990 requirements. Too many organizations choose not to grow or are operating in an atmosphere from 10 years ago when they didn’t have such regulatory oversight. Many not-for-profits have not kept pace with these changes,” Morrell said.

Such was the case with the ABA. “It had not developed a sustainable structure,” Morrell said. When he joined the board, it was not clear whether it could survive another two years, as it was also hit by the down market. Under his leadership, the organization has stabilized, paring its operating budget (now about $1.3 million annually) and staff, and hiring a new executive director. Membership numbers and finances are beginning to improve.

The ABA was formed about 43 years ago. It published its first

newsletter in 1969 as an eight-page mimeographed newsletter. It’s now Birding, a bi-monthly, award-winning, full-color magazine.

“The ABA was founded by the elite of birding and conservation, the giants of the field,” Morrell explained. “It was formed as a club for birders – listers – and only became a 501(c)(3) about 10 years later.” The ABA developed a code of ethics for birders and is known for its guides and definitive list of North American birds. It has even licensed bird-friendly coffee (shade grown).

Anyone who has seen the 2011 movie The Big Year will know about the ABA listing process and annual competition. In the comedy, Steve Martin and Jack Black try to defeat the cocksure, hyper-aggressive world record holder, played by Owen Wilson, in a year-long bird-spotting competition.

The ABA produces an annual publication of interested members' birding lists. The annual Big Day and List Report includes rankings of the total number of species ever recorded by an individual (a life list), as well as the number recorded over one calendar year (a big year), in one day (a big day) or in a particular region.

Morrell sees the ABA as a conservation group as much as a birding group and believes that the conservation field is too fragmented.

“The National Audubon Society is probably the most recognized conservation and birding organization in the United States; over the years, though, it began reducing its emphasis on birds and reframing itself as a conservation society,” he said. It had published an academic journal, North American Birds, but jettisoned it to the ABA. Today Audubon is working with the ABA to increase its focus on birding and bird conservation.

Morrell mentioned other important birding and conservation organizations, such as the American Ornithologists’ Union, which publishes The Auk and has a more scholarly bent; the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (research and citizen science); the American Bird Conservancy out of Washington (conservation and policy throughout the Americas), and UK-based BirdLife International, which has some 2.5 million members worldwide. Moreover, he said, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of regional and local birding and conservation groups throughout the country.

Morrell himself only joined the ABA in the 1990s, though he fell in love with birding about 41 years ago on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, where he eventually bought a home. Morrell is a member of the American Bird Conservancy, The Cornell Lab, New York City Audubon and, of course, the Carolina Bird Club.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates there are 45-65 million people who like to watch birds in this country,” Morrell said. Obviously not all of them belong to dues-paying organizations, but, Morrell added, the ABA, though it has only 11,500 members, in some way touches all 65 million birders.

Morrell foresees more partnerships among the groups, particularly for lobbying and advocacy. The ABA by its original charter was not able to advocate and lobby. Morrell moved for the membership to change that rule, as he feels that birders look to the ABA for advocacy on bird-related environmental and ecological issues. “During the Gulf oil spill, a lot of organizations came to us to be the voice of the community,” he noted.

Another ABA conservation initiative is its renowned “Birders’ Exchange” program, founded by leading birders Betty and Wayne Peterson of Massachusetts and still managed by Betty, which provides birding equipment, optics and educational material to scientists, educators and conservationists throughout South and Middle America and the Caribbean.

As the ABA’s finances stabilize, Morrell hopes the association will re-emphasize its youth programs, which include a highly competitive Young Birder of the Year contest and its ABA camp in Colorado. About 100 birders, ages 11 to 17, are expected this coming September in Wilmington at an ABA Youth Conference.

Another initiative is the creation of an American bird fair, modeled after the highly successful British Bird Fair. Started some 25 years ago by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and other conservation partners, the fair, an annual three-day mid-August event, attracts over 25,000 visitors and raises significant funds for conservation and habitat protection.

The ABA had begun thinking about creating a similar bird fair in the United States, but the consensus was that the birding community was too spread out for a successful fair here. “We’re asking ourselves again, can we develop a scenario where we can mimic the demographics of the British Bird Fair?” Morrell said. He hopes such a fair could happen in the next few years, probably based in the mid-Atlantic region, given the size and concentration of birders there.

“To do what we want to do, we need to be much larger,” Morrell said, adding that the ABA has only recently enhanced its member services and created a development function.

Why a Birder

“I call myself the ‘least’ birder on the board of the ABA,” Morrell said. “Among serious birders, I’m average. Among the 45 million, I’m in the top 5 percent.”

When he travels with his wife, Joan, a distinguished professor of behavioral neuroscience at Rutgers University, they enjoy birding but balance it with cultural aspects. They went on one trip to Scotland, for example, in which they listed 125 birds but also sampled 35 whiskies.

“The day after I retired, I went to Nebraska to see the sandhill cranes on the Platte River – 600,000 birds that arrive there for two to three weeks during their migration to the Arctic,” he said. “I could never do it before then, because the migration was at the end of the first quarter.”

And those were busy ends of quarters when he worked in Corporate Treasury. Among Morrell’s responsibilities were managing JPMC’s major capital investment policy, the guarantee and comfort letter policy and, with the legal department, the regulation with transactions with affiliates policy. He was a member of the Americas Reputation Risk, Americas and European New Products and Special Purpose Vehicle committees, and the Asset/Liability Committee for Chase USA, the company’s national credit card bank. A graduate of Carnegie Mellon with an MBA from the University of Rochester, Morrell began his banking career in the Analysis and Presentations Department of Chemical Bank.

He is currently a consultant and on the advisory board of The Regulatory Fundamentals Group LLC. As a Visiting Scholar at Rutgers, he provides still photography and video services documenting research at his wife’s laboratory.

Luckily his wife shares his love of birding.

“The pleasure of birding is being out in the field and the camaraderie with people,” he reflected. “Some of it is walking two hours in the Everglades or climbing a mountain to see the beauty of nature and the behavior of birds in the environment.”

Birders have included such luminaries as Jimmy Carter, Jonathan Franzen and the actress Jane Alexander – an ABA board member – and many from the JPMorgan Chase family, including Walt Shipley’s wife, Judy, whom Morrell first met at a presentation about the piping plover, and such eminent birders as Robert Lewis, Rich Cech, Brian Scammell, Tim Woodward and Rebekah Creshkoff.

“Birds are a barometer of the environment. If they’re not here, we’re not here. They’re the first indicator,” Morrell said. “What are they telling us now? They’re telling us about the loss of habitats, global warming, the deforestation of Brazil, land use changes and contamination. If you’ve seen birds for years somewhere and they are no longer there, you have to ask what changes have occurred in our environment.”

Morrell, by the way, eats poultry and has no problem with people who hunt fowl and eat what they take. “Ducks Unlimited, a major hunting and conservation group, has probably saved more wetlands than anyone. I am against trophy hunting for pure sport and think that the killing/taking of specimens for research is unnecessary, but sometimes hunting is necessary – for example, culling the overpopulation of Canadian geese, which is a problem much of our own making.”

He is angered when people complain about birds near airports that are built near flyways – “so what do you expect?” he asks. Similarly, wind energy groups that see themselves as environmentalists have to work with the wildlife conservation groups on how to reduce the impact on birds. “Conservation groups may have objections – but they also have solutions to reduce bird kill,” he said.

“For many years, the only way you could study birds was to shoot them,” he said. “Audubon had to shoot them to draw them. Collection added great knowledge - that’s how ornithology was done. You can learn a lot from specimen study and seeing the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History. But it’s not needed now. With the advent of better live capture techniques and DNA studies, you don’t have to kill the bird for research. You can use GPS for migration studies.”

Morrell’s own favorite bird is the merganser, whether common (see photo), red-breasted or hooded, a fish-eating duck that is a beautiful diver. His license plate is MERGANSR and he collects merganser decoys.

For all his activity in the birding world, he still has a hand in the theater and is trying to find solutions for what he calls “Neverland” companies that don’t have sufficient scale and yet must deal with all the structural, governance and financial issues that larger companies face.

He’s exploring with interested parties how to develop a common back office function for various performing arts companies and says he’s met with some Broadway producers who are somewhat interested.

“It would be great to have a real estate guy with extra space, to meet the rehearsal and office space these companies need,” he said.

Anyone with that extra space, or an interest in the American Birding Association, can contact Morrell.