A Personal Recollection of the Penn Square Bank Failure, 1982-1985

A Personal Recollection of the Penn Square Bank Failure, 1982-1985

Ed Moran Remembers

I’ve been asked to write a short history of the Penn Square days, and with the passing of one of the stalwarts of our merry band of draftees, Tom Jordan, I think it’s an appropriate time to do so.

The Penn Square Bank in Oklahoma City failed July 5, 1982. Eight days later, a dozen Chase and Milbank types arrived on the Chase plane to assess the damages. I think that most of us thought it would be a matter of months before we would be back in New York City; for some of us, it was a matter of years.

One of the lawyers from Milbank had been in an advance party. Upon finding the bank he reported back, “It’s in the back of a shopping center!!” That shopping center bank had made two billion dollars of loans to local wildcatters and participated virtually all of them out to five banks: Continental Illinois, SeaFirst, Michigan National, Northern Trust and Chase Manhattan. By the time the dust had settled several years later, the first three banks had been absorbed by other banks to keep them from failing. Chase had one of the lowest total participations, about $275 million; Continental was clearly the big (sick) gorilla – $1 billion.

We quickly set up four teams of bankers in offices borrowed from our local attorneys. The numbers fluctuated, but, at the high point, we had about 33 people in the task force consisting of bankers from Chase and lawyers from Milbank. I led the Chase group; Barry Radick led the Milbank group. The pressure was palpable from the beginning because Chase was also trying to extricate itself from its exposure to another small institution, a broker dealer, Drysdale Government Securities. The combination was catnip for the regulators, the press and the Wall Street analysts. Fortune wondered in a cover story whether this was the beginning of the end for Chase.

In contrast to the pressure from New York, the pace in Oklahoma City was glacial. The FDIC, having taken over Penn Square, had not a clue as to their next move. It quickly became apparent that they had never dealt with this type of bank: $2 billion in oil and gas loans that were more than 90% participated upstream. Their first two moves were beauties. They hired the law firm that had closed most of these loans and banned the participating banks from access to the loan files. So the lawsuits began. After a few weeks they relented and let us in the bank to copy the files but maintained that all contact with the borrowers had to go through FDIC personnel, some of whom were former bank employees with their own agenda. It was only after a month of negotiation that we convinced the FDIC to transfer the lead status to the individual banks.

One example of the difficulty of working with the FDIC? About six months after we set up shop, I received a call. Please allow the head examiner from the Comptroller's Office to look at our file copies, because the FDIC wouldn’t let him look at the originals. His team had been kicked out when the FDIC had come in, and he had never been able to finish the audit.

It was decided that there would be weekly meetings between the heads of each bank’s task force to form plans of action for each of the borrowers. In the beginning, this group was chaired by the Continental rep – an EVP, in keeping with their massive exposure. That bank and SeaFirst, also a big player, were of the opinion that most borrowers should receive additional credit facilities to “drill their way out of trouble”. Chase and Northern, with smaller exposure and increasing suspicions of the creditworthiness of the borrowers, were dead set against this approach. I don’t think we ever figured out where Michigan National stood: For the first three meetings they came with five people who then discussed among themselves who would sit at the table and who would occupy the back benches. Each week the bank sent a different group of people who would proceed to disavow what the previous group had said, and then they stopped coming altogether.

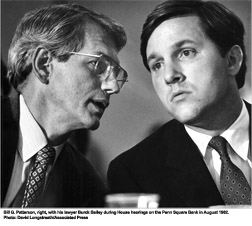

As might be imagined, with Bill Patterson (the boy EVP who drank beer out of his cowboy boots) at the head of the bank’s oil and gas division, Penn Square’s documentation was a mess. He was in the habit of crediting customers’ accounts with loan proceeds without informing the customer. This had the effect of some interesting conversations: “My records show...well my records show...well, show me the note...that’s not my signature,” etc, etc. The most outstanding example of this was the guarantee of a $31,500,000 loan to the No Sub S shell corporation:

As might be imagined, with Bill Patterson (the boy EVP who drank beer out of his cowboy boots) at the head of the bank’s oil and gas division, Penn Square’s documentation was a mess. He was in the habit of crediting customers’ accounts with loan proceeds without informing the customer. This had the effect of some interesting conversations: “My records show...well my records show...well, show me the note...that’s not my signature,” etc, etc. The most outstanding example of this was the guarantee of a $31,500,000 loan to the No Sub S shell corporation:

“Why do you call it that?”

“Because it’s not a Sub S corporation.”

“Oh.”

The guarantee was originally for $30,500,000, but the zero had been altered in pen to form a one and then initialed by someone, probably Patterson. Because Oklahoma law said that a guarantee was void if altered in a “material” way, it led to the almost Talmudic discussion of when is one million dollars a material sum of money. We settled this and other loans to a borrower nicknamed “Deep Gas” by swapping loans for interests in gas wells. He should have been nicknamed “Deep Hole”.

Chase’s Petroleum Department, partly to show they had absolutely nothing to do with making those loans, lent us a number of good people and several petroleum engineers. Two of them, although brothers, seriously disagreed on the pronunciation of their last name. Anything they said on oil and gas matters was therefore viewed with suspicion.

Continental Illinois was so enamoured of the business that they opened a loan production office about nine months after the failure of Penn Square. The president of their bank journeyed from Chicago for the grand opening party, to which I was invited. I reported back to our group the next night at our daily six o’clock meeting that I met everyone that we were in the process of suing.

Discussions between our people and our lawyers from OKC and Tulsa were lively at times. “Y’all lent money to him!” One of our young financial analysts took a swing at one of our OKC attorneys one day in a small dispute about legal strategy.

There were no direct flights between OKC and NYC: Change at Dallas, St. Louis or Chicago. At one of the quarterly reviews at One Chase, I suggested to Bill Butcher that we ban all loans made to cities requiring a change of planes. The missed connection stories multiplied as the routine became routine. One young lady missed her flight because she was so engrossed in a book, she didn’t hear the flight called. I missed a tight connection one Monday because over the weekend American had taken over the Braniff terminal and now Gate 28 was a half mile and three moving sidewalks from Gate 24.

Two of the players in Penn Square were Carl Swan and J.D. Allen, and Chase had a big exposure to a number of their joint ventures. By chance at the time, the N.Y Mets had two pitchers by the same last names. One day, in the interoffice mail from “the boss” Paul Walker, I received a clipping from the Daily News, “Swan and Allen Combine for Three Hitter” and a notation from PTW: “What’s going on down there?”

While comparing paperwork with several of the banks who participated in a rig construction loan, we couldn’t account for one of the six rigs pledged. The borrower finally admitted he didn’t have the rig; he had bought an airplane instead – hereafter to be known as “the flying rig.”

In reviewing a borrower’s financial statement one day, I asked where the Rolls was. It was widely known that this guy parked this big white Rolls Royce outside every bar in town. Well it turned out that after one of his all-night sojourns, he decided to use it to round up cattle on his ranch, drove it over a big rock and tore out the undercarriage of the car.

Despite the quality of the borrowers, I think we only threw two people out of our offices. One was the in-house counsel for the FDIC; the other was the “out house” counsel for one of the borrowers, a homburg-wearing silk-scarf type named Steve Jones, who later became infamous for defending Timothy McVeigh. (Later when asked about co-conspirators, McVeigh said that if he had any accomplices on the outside, Steve Jones would be a dead man.)

Oklahoma City became increasingly depressed after 1982. What started as a one-off happening at an unsophisticated small bank spread as the price of oil plummeted from $40 to $10. Gridlock set in as bills weren’t paid and loans weren’t repaid. By the late 1980s, most of the banks in the state had been taken over by the FDIC or merged with each other. Even the venerable First National Bank was restructured and sold. The downtown area became increasingly like a ghost town, a feeling intensified by the existence of a number of underground walkways connecting the buildings. The local drugstore was dubbed “the Chapter 11 drugstore” because it had only one row of product on most shelves; then it had none. Eating at restaurants was increasingly an adventure...“Why don’t you tell us what you do have today?”

Local bumper stickers that said “Stay Alive ‘Til ‘85” became outdated. Many good people suffered unemployment and foreclosures because, unlike Dallas, Houston and even Tulsa, OKC had one business – oil and gas. By the time that the Murrah Building was destroyed in 1995, both of the downtown hotels had closed. Ironically, it was that tragedy that started to turn the city around, and OKC is a far different and more diversified city now.

I have omitted naming the members of the task force because, if I started, I wouldn’t know where to stop. Most were draftees from various areas of the bank. In total there were about 35 Chase people. Some stayed for six months, some stayed for much longer. All endured the five- to six-hour commute home every other weekend (not counting tornadoes in OKC and snow in NYC). Most every evening, we broke out the beer and crackers at the six o’clock meeting and discussed the day’s events and what the other banks were doing and what our strategies would be. Everyone worked hard, and we had our share of fun as well. The Mash Farewell party was one of the high points of the after hours diversions.

To this day, I’m not sure what the final recovery was. We exchanged loans for cash, for oil and gas assets, for real estate – for anything that made more sense than what we had. The payout on these assets took many years, but I believe was better than the hand we were dealt.

I left the bank in August 1985 to take over a trust formed from the assets of one of the borrowers/board members of the bank, Carl Swan. He had been described by Mark Singer in his book Funny Money as having a “solid-member-of-the-posse look about him.” That about nails it… and nailed me to many more trips to OKC.

There are two good books about Penn Square: Mark Singer’s and Phil Zweig’s Belly Up. Radick and I talked to one or both of these authors while they were doing their research.

* * *

Anyone wishing to add recollections or comments should send them to news@chasealum.org.