A Moment in Bank History

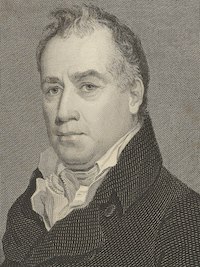

Charles John Michael De Wolf (1747-1806) of Antwerp

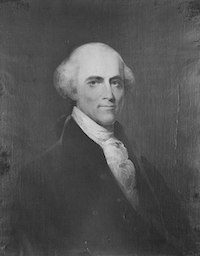

and John Quincy Adams (1767-1848):

and John Quincy Adams (1767-1848):

The American position regarding the loan raised in Antwerp,

or fairness as understood by the American government.

or fairness as understood by the American government.

More Research by Smits and Borremans of CAA Antwerp

On the occasion of the 2019 annual luncheon of the Antwerp chapter of the Chase Alumni, Josse Borremans (left) gave a presentation entitled “Which Chase subsidiary laid the foundations of the prime credit standing of the United States?”. The answer was the predecessor bank to Banque de

On the occasion of the 2019 annual luncheon of the Antwerp chapter of the Chase Alumni, Josse Borremans (left) gave a presentation entitled “Which Chase subsidiary laid the foundations of the prime credit standing of the United States?”. The answer was the predecessor bank to Banque de  Commerce: De Wolf & Cie. Josse‘s claim was confirmed by financial history scholars at Yale University.

Commerce: De Wolf & Cie. Josse‘s claim was confirmed by financial history scholars at Yale University. PART 1 (summarized below) discussed the relationship and deals among Charles De Wolf, the young John Quincy Adams (then the U.S. Envoy to The Hague) and Gouverneur Morris, among others.

Marc Smits (right) and Borremans have done further research, resulting in this paper, filled with financial and political history and intrigue.

* * *

1. Review and New Information

The previous article was based on research performed by Belgian Chase Alumni Marc Smits and Josse Borremans regarding the American business of Charles John Michael De Wolf (1747-1806).

De Wolf, a self-made banker, was the founder and proprietor of Bank De Wolf, the predecessor of Banque de Commerce, which was, at one time, a Chase affiliate in Belgium. De Wolf strongly believed that he was invested with the mission “to assure that the financial future of the United States of America would be honorable”. Regarding his “mission”, which he achieved with some measure of success, scholars at Yale University expressed the opinion that the certificates, a financial derivative instrument “invented” by De Wolf, can indeed be considered as one of the steps in establishing the prime credit standing of the United States.

As a banker, De Wolf was full of contradictions. On the one hand, he used conservative credit judgment and was very analytical and authoritarian vis-à-vis his clients; his understanding of banking was that it had to be exercised in respect of time-honored customs and traditions. For him, banking was not a hobby but a craft in the way any other craft was organized, understood and exercised by the middle class from which he came.

On the other hand, this conservative, prudent man became extremely belligerent when he was competing against the Amsterdam bankers, especially in conjunction with the United States. He then turned into an extremely aggressive banker and, even worse, was negligent with serious faults in his due diligence. The most typical example of such behavior was his purchase of 440,000 acres of land in northern New York along the Saint Lawrence River. He never implemented his plan to develop these lands and never had them surveyed by professionals, which was extremely speculative and unprofessional. When he realized that there was no quick possibility to exit at a profit, he had no moral objections in shifting the risks to his “capitalists”. His objective was to collect 1,200,000 Brabantine guilders in the market, but he could only collect 820,000. The prospectus described the land as a Garden of Eden and an ideal location for a major port. De Wolf further demonstrated his tricky side as a merchant banker – shifting the risks to the investors, locking in his profit and keeping part of the upward potential. He also restored his liquidity and remained the recorded owner of the land.

In 1791, he also provided a loan to the tune of 3,000,000 Brabantine guilders to the Federal government; through Gouverneur Morris (left)(1752-1816) – constitutionalist, merchant, diplomat, intellectual, political conspirator in France, master speculator, fixer and libertine in Europe – he invested in American Liquidated Debt (6% tranche). Once again, he shifted most of the risks to his investors. The fact that he could easily do this is an indication that his “capitalists” trusted him. De Wolf also had the unfortunate habit of becoming rather disagreeable when someone asked important, discerning questions.

In 1791, he also provided a loan to the tune of 3,000,000 Brabantine guilders to the Federal government; through Gouverneur Morris (left)(1752-1816) – constitutionalist, merchant, diplomat, intellectual, political conspirator in France, master speculator, fixer and libertine in Europe – he invested in American Liquidated Debt (6% tranche). Once again, he shifted most of the risks to his investors. The fact that he could easily do this is an indication that his “capitalists” trusted him. De Wolf also had the unfortunate habit of becoming rather disagreeable when someone asked important, discerning questions. Based on the contents of 156 documents consisting of contracts, letters, account statements and other documents sent by De Wolf to Gouverneur Morris, we formed the opinion that De Wolf was caught in a state of tunnel vision. Furthermore, based on circumstantial evidence, we concluded that Gouverneur Morris framed De Wolf – but why would Gouverneur Morris want to do this? The answer was to become rich, and De Wolf was an easy target. In essence, these findings still hold. Gouverneur Morris made considerable profits for illusionary services rendered to De Wolf, but De Wolf certainly had to also be blamed for his lack of due diligence.

Of course, we realize that, as we didn’t find any of Gouverneur Morris’s letters to De Wolf to counter our view, our opinion was potentially biased. Moreover, was Gouverneur Morris’s flamboyant personality and mode of operating really representative of the position of the American Government as De Wolf assumed? We realized that this generalization required more serious evidence. Once again, mere luck compensated for our lack of expertise as financial historians. This time it came in the form of extraordinarily helpful librarians at the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS), the Connecticut Historical Society (CHS) and the Library of Congress (LOC), as well as at Westmalle Abbey, not far from Antwerp, Belgium. The librarians not only guided us to the original letters De Wolf sent to John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) when the latter was Resident Minister of the United States in The Hague (Netherlands/Batavian Republic), but we also received access to Adams’s letter books, with copies of all outgoing letters. Furthermore, we also found copies of the letters sent by the second U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Oliver Wolcott Jr. (1760-1830), to De Wolf. The reports sent by Adams to the State Department and the Treasury Department, including copies of his correspondence with the Amsterdam bankers of the United States, were equally interesting. Applying historical critique to this material considerably improved the reliability of our findings and generalizations. These new, unexpected sources forced us to reconsider our view of De Wolf, but even more so of the Government of the United States; Gouverneur Morris was definitely not representative of the U.S. government.

2. The Adams Brothers in The Hague and Charles John Michael De Wolf in Antwerp

After graduating from Harvard College, John Quincy Adams (left) became a lawyer. At age 26, he was appointed Minister to the Netherlands It was his first important assignment in the Foreign Service. He knew the Netherlands from the days when his father, John Adams (1735-1825), represented the United States in The Hague. (His brother Thomas Boylston Adams (1775-1832) acted as Secretary to the small American diplomatic mission and, during Adams’s mission to London on behalf of the State Department, acted as chargé d’affaires.)

After graduating from Harvard College, John Quincy Adams (left) became a lawyer. At age 26, he was appointed Minister to the Netherlands It was his first important assignment in the Foreign Service. He knew the Netherlands from the days when his father, John Adams (1735-1825), represented the United States in The Hague. (His brother Thomas Boylston Adams (1775-1832) acted as Secretary to the small American diplomatic mission and, during Adams’s mission to London on behalf of the State Department, acted as chargé d’affaires.)The Netherlands, or the Batavian Republic as it was then named, had terminated the hereditary privileges of the Princes of Orange as Stadtholder in a bloodless revolution. It was a republic with the function of Head of State collectively assumed by the States General; there was no individual President. France’s influence was on the rise in Europe, and the Dutch colonies were temporarily confiscated by Great Britain. Trade and commerce were in decline, but Amsterdam was still the most important financial center on the European Continent.

For the financial transactions of the United States in Europe, the relationship with the Amsterdam banking firm of Willink and Staphorst (Wilhelm and Jan Willink, Nicolaas and Jacob van Staphorst, and Nicholas Hubbard) was extremely important. In London, the United States banked with Bird, Savage and Bird, but that firm was less solid than Willink and Staphorst. Simply put, it was the principal working banking relation that America could rely on in late 18th century in Europe. This relationship started after the victory at Yorktown (October 19, 1781). It was broadly based: Willink and Staphorst knew personally prominent Americans and several Cabinet members in the American government. John Adams (1735-1826) still maintained a “savings account” at the bank, with a balance of £3580, in that period. Willink and Staphorst supported the United States causes in bad times, but in 1795 they became less flexible because of the wars in Europe and rising tensions between France and the United States.

The situation in Western Europe became extraordinarily complicated. France exported its revolution outside of France and considerably extended its borders to the north and east and in Italy. As a consequence of the annexation by France of the Southern Low Countries, De Wolf officially became a French citizen, although “subject” might be a better term. French occupation was particularly harsh: The City of Antwerp was charged money to pay for its liberation, with nobility and religion persecuted in the name of equality, and the goddess “Reason” replacing superstitious religious beliefs. Gold and silver objects and works of art were confiscated in large quantities and taken to France as spoils of war, and young men were drafted into the French armies. De Wolf was taken hostage on at least three occasions, yet what he hated most was that he had to provide lodgings in his house to French officers; the risks of having a lot of cash was in his home/Counter and his young wife of 23 mingling with French officers were his major causes of dissatisfaction with the French “liberators”.

Banking was not booming. Because of the war against the French Republic, the usual borrowers – the Russian Czar, the Habsburg Crown Countries, the Kingdom of Sweden, German states of all sizes – had stopped their payments of interest and principal on loans raised, directly or indirectly, in Antwerp and Brussels. In fact, there was only one country that was still paying under its “new money commitments”: the United States of America. These New Commitments consisted of a couple of loans placed by Willink and Staphorst and the Antwerp Loan placed by De Wolf.

Remittances by the American government to service these loans were not only subject to the usual perils of the sea but also additional problems because of the war. The Royal Navy hindered all navigation with France and the states under French influence. To retaliate, France did its utmost to close all European ports for English trade. Alliances changed according to the hazards and changing fortunes of war. American commercial relations with Great Britain improved after the signing of the Commerce Treaty negotiated by John Jay (1745-1829) in 1794. Unsurprisingly, the Treaty was not appreciated by France; its dissatisfaction with the ungrateful Americans escalated to “The Quasi-War” of 1798-1801 with the United States. From a complexity viewpoint, it was a changeable landscape.

Only the free imperial city of Hamburg was more or less open for business and acted as a go-between for international payments. The American consul in Hamburg, John Parish, played a key role as facilitator for the remittances by the American government to the rest of Europe in general and Willink and Staphorst in particular. His son David Parish represented the firm in Antwerp.

3. De Wolf contacts Adams

De Wolf’s first letter to Adams is dated March 16, 1795. It is written in French, a language that Adams had mastered perfectly. De Wolf referred to “his” loan of 1791. He wrote that the interest had been paid very regularly but, in terms of the maturity of the principal as of December 1, 1794, only 30,000 Brabantine guilders (out of the 92,250 due) had been paid. De Wolf knew that for Willink and Staphorst, the interest maturities of January 1, February 1 and even March 1, 1795 had been honored: so why not the same for him? De Wolf, as always, was very critical of Willink and Staphorst because, had they informed him in November of payment delays, De Wolf, always able and willing where the United States was concerned, would have had the cash to pay the interest to his investors. In March 1795, however, this was no longer possible because of a shortage of money in cash. Yet De Wolf, in contradiction to the argument that cash was scarce, proposed to issue a new loan in Antwerp. This is part of his usual game of “the friendly U.S. banker at Antwerp” versus the bad bankers at Amsterdam.

On a more personal note, De Wolf requested Adams, the U.S. envoy in The Hague, to obtain an agreement from the French authorities that he, De Wolf – a French citizen – be exempt from lodging French officers; his status as banker to the United States of America necessitated this as he was holding cash money paid by that country. This was completely unrealistic but entirely consistent with the expectations he held equally vis-à-vis Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816) on other similar occasions. One address for all his problems!

De Wolf’s second letter is dated March 30, 1795, this time in English. He mentions that the reputation of the United States hadn’t suffered at all from the partially unpaid interest because “everybody was persuaded of the solidity of this stock and attributed such delay only to circumstances and irregularities of post and navigation”. Thanks to De Wolf, the credit standing of the United States continued to be first rate. De Wolf once more asked to be considered by the United States if and when they decided to return to the European market to borrow money.

4. Adams presents the new American Plan and clarifies the American position regarding its new money debt

Adams’s reply to De Wolf is dated March 22, 1795 and brings good news: De Wolf is authorized to draw bills of exchange on Willink and Staphorst for the unpaid balance of December 1, 1794. Adams insists on the fact that the delay in payment was solely due to the “state of war and interruption of intercourse between this country and yours”. As for raising new money in Antwerp, Adams considered that it would be impracticable for a long time. In short, despite these extraordinarily difficult times, the American loan in Antwerp was current again in principal and interest. As expected, Adams wrote that getting the French officers out of De Wolf’s house was not within his power.

A wise banker would be satisfied with a return to normalcy, but not De Wolf. On April 19, 1795, he expressed his profound disappointment that “his status as banker of the United States is not a valid reason for intervention with the French government regarding the French officers lodged in his house”. But he also recognized a similar-minded person in Adams’s method of tackling a problem – analytically, with an eye for detail. So, De Wolf reacts with details of how he applied the partial interest payment.

De Wolf wrote that he bought American bonds from panicking investors well below “the market price”. The partial payment on the interest of December 1 was first used to pay all interest on the bonds he held in his investment portfolio. The remaining balance of one-third (about 10,000 Guilders) was then paid to other bondholders. This could only be right if he held two-thirds of the original issue, and that is impossible. The technical questions Adams asked in the subsequent months, made it clear that he and the Treasury wanted the investors to be treated fairly. Ultimately, they were providing the funds to the United States, and the Americans had the strange idea that the creditors had to be treated equitably.

Nevertheless, the U.S. Treasury Department got more and more frustrated by the fact the United States had to pay important transaction costs and ran the exchange risk on all payments. The U.S. Treasury’s interpretation of the Loan Documentation (in Flemish) was that its contractual commitment was to pay in U.S. Dollars. In theory it had no exchange risk provided the Treasury could transfer the dollars to Europe, but that it couldn’t do: As a monetary union, the U.S. Dollar was still a work in progress. The possibility of remitting money was also a function of international trade and/or direct investment. At the time, the United States had a negative trade balance, and foreign direct investments in the United States were very limited.

There was a sort of proto-eurodollar market derived from the 6 tranche of the American Liquidated Debt arrangement. That debt was actively traded in London, Amsterdam and other places, thus offering arbitrage opportunities. Prices were extremely volatile and fluctuated between 5 cents on the U.S. Dollar and par. These notes were occasionally used to pay large amounts in USD. De Wolf used this possibility to pay USD 100,000 as partial payment for his real estate purchase in the State of New York. The U.S. Embassy in The Hague had at its disposal with Willink and Staphorst an unspecified amount of 6 percent notes to be sold for cash if and when they might be cut off from the United States for a long period of time.

In the real-life situation, the USA ran the exchange risk/profit on the USD versus the Dutch Guilder for the Amsterdam loans. In the case of the Antwerp Loan, the exchange risk was double USD/Dutch Guilder and Dutch Guilder/Brabantine Guilder, because all payments transited through Willink and Staphorst before making it to Antwerp.

The Treasury Department intended to get rid of this problem, so it presented a Plan to the Amsterdam Bankers and De Wolf. In short, they proposed to convert foreign debt into domestic debt by offering compensating advantages to the bondholders. The coupon rate would be increased from 4.5 to 5 percent, with interest paid quarterly instead of annually. A second “advantage” for the investor was the USD/Brabantine guilder exchange rate. The USD was valued at 50 stivers or 2.5 Brabantine guilder, which, in consideration of the theoretical rate determined by the Treasury, was rather advantageous for the guilder – estimated by Adams at 10 percent per annum. This was clearly an error.

Early in 1795 the Treasury got the news that De Wolf, once more, had been arrested by the French occupiers. Treasury Secretary Wolcott (left) sent a most courteous letter to De Wolf dated April 17, 1795: “Reports have reached this country, that your Compting (sic)/Counting House has been shut up, and your personal liberty restrained by the French government to secure payment of a contribution imposed upon the City of Antwerp…I can assure you that I see nothing in this event which might impair my confidence in your character, on the contrary it may perhaps be justly viewed as an evidence of your general credit, so far as it may prove a personal misfortune.”

Early in 1795 the Treasury got the news that De Wolf, once more, had been arrested by the French occupiers. Treasury Secretary Wolcott (left) sent a most courteous letter to De Wolf dated April 17, 1795: “Reports have reached this country, that your Compting (sic)/Counting House has been shut up, and your personal liberty restrained by the French government to secure payment of a contribution imposed upon the City of Antwerp…I can assure you that I see nothing in this event which might impair my confidence in your character, on the contrary it may perhaps be justly viewed as an evidence of your general credit, so far as it may prove a personal misfortune.”This letter made it to Antwerp in early July at a time when Adams had started to explain to De Wolf the American plan regarding the conversion of the foreign debt. In all probability, De Wolf interpreted Wolcott’s letter as an indication that the Americans would not put him under extreme pressure if he complained hard enough about the hardships he had to endure. He regularly complained, but he also explained in a rational, professional way why the American Plan was unacceptable for the majority of the bondholders.

De Wolf’s principal objection was the administrative burden to be complied with in a country far away and overseas. The existing bonds had to be collected and sent with a declaration of ownership to the Treasury Department in Philadelphia. There the USD counter value of each bond would be inscribed in the Great Ledger of the Treasury Department, and, subsequently, new nominative USD bonds would be returned to Antwerp. Consequently, there was a period – in ideal circumstances of at least five to six months – that the bondholder was left empty handed. In consideration of the perils of the sea and the war(s) in Europe, that uncertainty was psychologically very difficult for the creditors to accept.

5. Adams’s defense of the Plan

De Wolf had other serious reservations of a more personal nature regarding the Plan. Not only did it considerably diminish a lucrative collateral business, but he would have to perform a lot of unpaid work. Moreover, he was requested to explain the complex deal to his clients. De Wolf’s normal way to talk to his clients was to give them only few details and demand the clients’ trust. His motto was, “I know what I am doing.” So, for De Wolf, this was a tricky situation. He realized that if risks materialized during the extended period needed to finalize the conversion, the bondholders’ anger and grief would be directed against him. So, he wasn’t overwhelmingly enthusiastic to sell this deal to his clients. On two occasions he wrote Adams stating that, in his professional opinion, the bondholders would not accept the deal.

But the 28-years-old Adams didn’t intend to drop the case without a fight. On July 12, 1795 he started a four-page letter to De Wolf. On August 16, 1795 he completed this letter with a number of strict instructions to De Wolf, as he did with Willink and Staphorst, to inform the creditors and go public with the Plan. This had to be done with a large advertisement in local newspapers. We found a copy of the advert in the Antwerp Gazette of September 29, 1795, which is shown as an exhibit.

Our very short summary can’t give full credit to Adams’s well written defense of the Plan. Basically, he states that any well-informed creditor should accept it out of self-interest. Firstly, there is the absolute certainty that the amounts due will be paid punctually (in America). Secondly, there are the compensating interest and principal payments that Adams estimated, rather unrealistically, at 10 percent for the creditors. Thirdly, the United States cut the paperwork and personal inconveniences for the creditors to the minimum: Registration of their bonds with the Treasury and exchange of the old bonds for new ones could be done by De Wolf’s American correspondent.

But Adams’s principal argument was that of the European context of war and its many hazards. Not only were the Royal Navy and the mounting tensions between France and the United States serious obstructions to free trade and capital movements, but also nations like Holland, Denmark, Sweden and others – none of them at war with the United States – regularly intercepted American ships, confiscated their cargoes and molested their crews. Moreover, alliances on the European continent changed according to the hazards and fortunes of war. Given this context, the United States simply couldn’t guarantee punctual payment. Such a guarantee would oblige the United States to maintain huge reserves in foreign currencies, which they didn’t have, with banks all over Europe, and that would be an unrealistic and unreasonable demand.

With certain reservations, Willink and Staphorst and De Wolf agreed to explain and defend the Plan. Both banking houses inform Adams that a majority of the shareholders rejected the Plan. De Wolf maintained his position detailed in his letters of July 27, August 13 and August 26, 1795. The advert we found in the Antwerp Gazette, however, is dated September 29, 1795, a month after De Wolf informed Adams that the bondholders had overwhelmingly rejected the Plan. Yet the advert stipulates that De Wolf will explain the details of the Plan in a face-to-face conversation with each interested bondholder. We can conclude that De Wolf didn’t defend the Plan, and neither he nor Willink and Staphorst organized an assembly of the bondholders formally voting on the matter.

With the benefit of hindsight, two important points were missed by De Wolf. First, there was the option that the Treasury demanded to prepay the loan at any time. Perhaps De Wolf considered this a minor risk in consideration of the U.S. government’s difficult financial situation. Second, neither De Wolf nor Adams gave any consideration to the fact that the Brabantine guilder was the currency of a country that no longer existed. Antwerp had become part of the French Republic. On August 15, 1795, the French National Assembly “created” the French franc to replace all other currencies in circulation in the French Republic.

6. “The smart ones left” (The CAA’s John A. Ward III in 1984)

De Wolf could have looked at the Plan as part of a solution to manage his problems. In summary, these were threefold:

-

he had 440,000 acres of land in New York that he had never seen or surveyed;

-

in the United States, he would be best placed to administer the American bonds and certificates, those of the 1791 issue as well as those of the Liquidated Debt; and

-

if he felt intimidated by the presence of French officers in his house, that risk didn’t exist in the United States.

Hence his interests would be best served by a move with a lot of cash, his beloved wife and a couple of his trusted clerks to the United States, but this he didn’t do.

Yet there was an Antwerp banker and a bondholder well-known to De Wolf who had reached that decision on his own. When the Plan was being discussed, Henri-Joseph Baron Stier d’Aertselaer (left) (1743-1821) had already settled in Maryland with his family and two servants. Officially Baron Stier was a banker like De Wolf, but in reality he was essentially managing the family assets, and these were substantial. De Wolf and de Stier were acquainted but were of a completely different breed. For De Wolf, Baron Stier was a hobbyist, not a real banker. For Baron Stier, De Wolf was a commoner without pedigree and lacking in culture.

Yet there was an Antwerp banker and a bondholder well-known to De Wolf who had reached that decision on his own. When the Plan was being discussed, Henri-Joseph Baron Stier d’Aertselaer (left) (1743-1821) had already settled in Maryland with his family and two servants. Officially Baron Stier was a banker like De Wolf, but in reality he was essentially managing the family assets, and these were substantial. De Wolf and de Stier were acquainted but were of a completely different breed. For De Wolf, Baron Stier was a hobbyist, not a real banker. For Baron Stier, De Wolf was a commoner without pedigree and lacking in culture.The Belgian Stier family had been rich for five generations. They owned two castles, a “City Palace” in Antwerp and many smaller properties with tenants. The family tradition dictated that the boys study at university. The girls received the best possible education available in Europe, which, at the time, was the exclusive and highly international Convent College of the English Canonesses in Bruges. The Stier family also possessed a collection of 68 paintings by Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian, Brueghel and van Dyke with an impeccable provenance, starting with Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) painter and art collector. Baron Stier considered it his moral duty to protect these works of art from confiscation by the French.

Like De Wolf, Baron Stier had seen the French occupation in action and didn’t like it. But he acted, preparing his departure and instructing his agents in Amsterdam and London to sell assets for cash. The family set sail in the summer of 1794 for the United States with a lot of cash and their art collection; the parents, their eldest daughter and her husband, their son and his wife, and the youngest Stier daughter, Rosalie (1778-1821), age 16, plus two servants.

The family first settled in Annapolis and mingled easily with the American elite, including George and Martha Washington. They bought a tobacco plantation and built Riversdale Mansion at Bladensburg, MD, near Washington, DC. The youngest daughter, Rosalie (left), married George Calvert (1768-1838), a plantation owner. After the rest of the family returned to Europe she took charge of the completion of Riversdale with her father’s financial support. She also managed the American assets of her family. Stier-Calvert had considerable discretionary powers but invested essentially in U.S. government bonds, road companies and bank stocks. When she died in 1821, the assets managed for her European relatives amounted to USD 248,000.

The family first settled in Annapolis and mingled easily with the American elite, including George and Martha Washington. They bought a tobacco plantation and built Riversdale Mansion at Bladensburg, MD, near Washington, DC. The youngest daughter, Rosalie (left), married George Calvert (1768-1838), a plantation owner. After the rest of the family returned to Europe she took charge of the completion of Riversdale with her father’s financial support. She also managed the American assets of her family. Stier-Calvert had considerable discretionary powers but invested essentially in U.S. government bonds, road companies and bank stocks. When she died in 1821, the assets managed for her European relatives amounted to USD 248,000. Moving to the United States wasn’t a guarantee of happiness and a healthy life but it was the best way for De Wolf to manage his American assets. A good alternative would have been to entrust this mission to one of his associates.

As the late John Ward, former president of the Chase Alumni Association, put it, "The smart ones left."

7. John Quincy Adams chatting with De Wolf

We are now in an ambiguous situation. On the one hand, De Wolf had written that most of the bondholders didn’t like the Plan. When he asked Adams how the Amsterdam bankers had reacted, the latter admitted that Willink and Staphorst had raised problems similar to De Wolf’s. The key question was whether the Americans would stick to the original Plan or amend it. In such a situation, one would expect that Adams would inform the Treasury and ask for (amended) instructions, which he did. Wolcott got the report probably mid-December 1795.

Awaiting the Treasury’s reaction, Adams started asking questions like “what if the interest rate were increased to 6 percent?“ But he also had a very close look at the Antwerp loan documentation. His command of Dutch being good, he could read and understand the original documents and the bonds. In the records, Adams found that William Short (1759-1849) had signed bonds for a total amount of 3,000,000 Brabantine guilders but only 2,050,000, were actually drawn. Where were the 950 bonds representing the undrawn amount? Adams also noticed that the account had been debited for the protest costs of a draft drawn by De Wolf in conjunction with American Liquidated Debt, legally only payable in the States.

De Wolf, realizing that he was discussing with a person with an eye for detail and an interest in finance, reacted immediately. He had the “mistakes” corrected that were due to clerical error and/or a poor translation of Flemish into English. It was time for De Wolf to chat about other issues. For the first and only time in his life, De Wolf wrote something positive about the French. They had forced the Dutch to terminate import duties on the cargo of ships sailing to Antwerp – excellent news. Would it not be a good idea to ship American tobacco to Antwerp with De Wolf as agent?

On August 14, 1795, De Wolf asked Adams what he thought about the evolution of land prices in the State of New York. Adams’s answer is dated August 17. He wrote, “… received reports from the United States that such land is believed to be most valuable, but ....I (Adams) have no knowledge upon the subject of this species of speculation beyond what is to be collected from common report.” De Wolf was nevertheless impressed by Adams’s no-nonsense approach and his good financial skills. Hence he had reason to be optimistic for the payment of the installment of December 1, 1795.

De Wolf started the procedure with his letter of October 8, 1795 asking Adams whether Willink and Staphorst allowed him to draw letters of exchange on them maturing December 1, 1795. The summarized conclusion of the exchange of correspondence between Adams and Willink and Staphorst is that they were only willing to allow De Wolf’s drafts if they had reasonable assurances that their installments of January 1, February 1 and March 1, 1796 also would be honored; this they did not have (yet).

Adams wrote on October 20 to De Wolf, “They (Willink and Staphorst) have received remittances not yet realized in cash…but as it is possible they may think other urgent claims require a different application of the money when they shall receive it, and consequently may decline answering your draft at this time.”

Adams reminded De Wolf that the purpose of the Plan and other proposals made by the United States was to avoid such incidents and assure punctual repayment of the debt. He wrote, “I know not what wrong interpretation the ignorant or the malicious can give to the offer…every person sufficiently informed to have a judicious opinion must consider it as truly generous.” Adams clearly got irritated by the role played by De Wolf in “killing the Plan”, but he blamed Willink and Staphorst more.

Adams also announced that he would temporarily leave The Hague on October 9 on an official mission. De Wolf would have to deal with his brother Thomas Boylston Adams.

8. Thomas Boylston Adams and De Wolf

With Adams temporarily gone, Thomas Boylston Adams (left) was promoted to chargé d’affaires for the United States in The Hague. Only 23 years old, he wanted to show “something” to his family and his elder brother on whom the Adams Family had placed all its confidence and expectations. Thomas Boylston and De Wolf performed the usual song and dance. De Wolf insisted, as he did on all previous occasions, that the honor and credit standing of the United States could only be safeguarded if the interest payments falling due on December 1, 1795 were paid punctually (letter of November 5, 1795). De Wolf also explained the advantages of sending the United States remittances directly to him instead of to Willink and Staphorst. This would promote him to a first-tier banker of the U.S. government.

With Adams temporarily gone, Thomas Boylston Adams (left) was promoted to chargé d’affaires for the United States in The Hague. Only 23 years old, he wanted to show “something” to his family and his elder brother on whom the Adams Family had placed all its confidence and expectations. Thomas Boylston and De Wolf performed the usual song and dance. De Wolf insisted, as he did on all previous occasions, that the honor and credit standing of the United States could only be safeguarded if the interest payments falling due on December 1, 1795 were paid punctually (letter of November 5, 1795). De Wolf also explained the advantages of sending the United States remittances directly to him instead of to Willink and Staphorst. This would promote him to a first-tier banker of the U.S. government.Thomas Boylston agreed that punctual payments were important, but he had to convince Willink and Staphorst. Awaiting their concurrence with De Wolf’s drafts, he attempted, in his turn, to convince De Wolf of the advantages of converting foreign debt into domestic debt (letters of October 20 and 24, 1795).

The younger Adams, also a graduate of Harvard College, turned out be a quick learner. With the deadline of December 1 approaching, he wrote to De Wolf that much of the delay was not due to the United States but rather in fact due to De Wolf’s troubled relations with Willink and Staphorst. So why would De Wolf not pay the interest to his clients and finance the United States for a short period of time?

On November 29, 1795, Thomas Boylston confirmed once more that Willink and Staphorst hadn’t changed their viewpoint and reiterated his request to De Wolf to finance the interest that was maturing a couple of days later. There was a big surprise on December 3 when De Wolf wrote to Thomas Boylston that Willink and Staphorst had authorized him to draw drafts on them for the full interest amount. The drafts, however, had to mature at 60 days sight. That could only mean that De Wolf contacted Willink and Staphorst directly and was able to convince them; De Wolf was capable of surmounting his personal feelings regarding them. All things considered, a reasonable compromise was reached between the two banking firms.

Encouraged by the solution found for the interest, Thomas Boylston wanted to continue his winning streak. In the coming months, he once more put on the table the conversion of the foreign debt into domestic debt. As could be expected, neither De Wolf nor Willink and Staphorst changed their previous positions. At the end of May 1796, John Quincy Adams was back in the Netherlands, but he had changed. Who or what had changed him?

9. Adams in London

The Secretary of State had ordered Adams to negotiate some amendments to the Commerce Treaty negotiated by John Jay. Clear instructions were promised, but they took a lot of time before making it to London. This short London episode was extremely important for both his future career and his private life.  Adams started courting Louisa Catherine Johnson (left) (1775-1852), his future wife and First Lady. If she had received the dowry of £5,000 promised by her father, she would have had options, but the Johnson family was virtually bankrupt. So Adams was the only suitable candidate to marry her without a dowry. Adams loved her very much, but he had unreasonable expectations as proven by the long reading list of books – not of the entertaining kind – that he assigned to her to compensate for some shortcomings in her formal schooling.

Adams started courting Louisa Catherine Johnson (left) (1775-1852), his future wife and First Lady. If she had received the dowry of £5,000 promised by her father, she would have had options, but the Johnson family was virtually bankrupt. So Adams was the only suitable candidate to marry her without a dowry. Adams loved her very much, but he had unreasonable expectations as proven by the long reading list of books – not of the entertaining kind – that he assigned to her to compensate for some shortcomings in her formal schooling.

Adams started courting Louisa Catherine Johnson (left) (1775-1852), his future wife and First Lady. If she had received the dowry of £5,000 promised by her father, she would have had options, but the Johnson family was virtually bankrupt. So Adams was the only suitable candidate to marry her without a dowry. Adams loved her very much, but he had unreasonable expectations as proven by the long reading list of books – not of the entertaining kind – that he assigned to her to compensate for some shortcomings in her formal schooling.

Adams started courting Louisa Catherine Johnson (left) (1775-1852), his future wife and First Lady. If she had received the dowry of £5,000 promised by her father, she would have had options, but the Johnson family was virtually bankrupt. So Adams was the only suitable candidate to marry her without a dowry. Adams loved her very much, but he had unreasonable expectations as proven by the long reading list of books – not of the entertaining kind – that he assigned to her to compensate for some shortcomings in her formal schooling.Louisa Catherine suffered from multiple health problems her entire life. In his diary, Adams often recorded that Louisa Catherine was “ill,” “very ill” or “badly ill.” Louisa Catherine was not the only one enduring a lot of stress; Adams also was in a depressive mood. Not only was there his complicated relationship with Louisa Catherine, but his father John Adams was running for President against Thomas Jefferson in the most bitterly contested U.S. election ever. In the course of 1796, the European press reported riots in the USA. On May 19, 1796, Adams noted in his diary: “The difference between the popular and Executive branches of the American Government is approaching a crisis, and I fear the superior force is not where it should be.”

CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE (Yes! There's more!)

10. Adams’s return to The Hague: the Bourne Ultimatum

11. Incidents leading to Adams’s loss of confidence in De Wolf

12. Closure: Eternal glory for Adams in 1815