The Merger Name Game

S ome time before the merger, I remember weekly meetings to make changes to the branch bank account offerings. Don Boudreau, who ran the Retail Bank, sat at the head of the table and I sat at the foot on the table. On one side were the marketing folks and on the other side were the systems people. Each week the marketing folks would describe the ideal account offerings. Each following week the systems folks would describe how these changes could be implemented, and the marketing folks would say that was not exactly what they intended. Then the cycle would repeat. My recollection was that when the project was over, the resulting account offerings looked suspiciously like those of Chemical Bank.

ome time before the merger, I remember weekly meetings to make changes to the branch bank account offerings. Don Boudreau, who ran the Retail Bank, sat at the head of the table and I sat at the foot on the table. On one side were the marketing folks and on the other side were the systems people. Each week the marketing folks would describe the ideal account offerings. Each following week the systems folks would describe how these changes could be implemented, and the marketing folks would say that was not exactly what they intended. Then the cycle would repeat. My recollection was that when the project was over, the resulting account offerings looked suspiciously like those of Chemical Bank.

Another episode around this time was the notion that the credit card for bank customers should have no annual fee. Prior to that the fee income was very substantial. There was a meeting between Don and Tom Lynch to discuss this change, where I was the only other person in the room (because of some outside research done for the Retail Bank). For me that was a rather uncomfortable meeting, since I had done work for both men and had great respect for them both, even though they had conflicting interests in this situation.

I’m curious to hear other people’s perspectives on these issues as they happened back then.

From Karl Schmidt (2/6/21): I worked at Chase from 1966 to 1996, mostly at the Corporate Finance Department at Head Office. As best as I could, I have also looked at Chase from an investor’s point of view related to my 401(k) plan.

From Karl Schmidt (2/6/21): I worked at Chase from 1966 to 1996, mostly at the Corporate Finance Department at Head Office. As best as I could, I have also looked at Chase from an investor’s point of view related to my 401(k) plan.

As we were approaching the early 1990s, many U.S. banks, especially the large U.S. money center banks, were suffering from a significant exposure to non-performing LDC (Less Developed Countries) loans, erroneously thinking that sovereign countries don’t go bankrupt. Further, Chase had a sizable non-performing commercial real estate loan portfolio. Wall Street lead analysts were mostly negative on those banks, with the result that their common stock prices were trading at mid-single digits P/E's and also at or below tangible book (now at P/E’s between 12 and 15 and at or above tangible book).

Back to the early 1990s: Chase was one of those vulnerable banks, and its stock price probably with a good upside potential. In came Wall Street activists, such as Michael Price of Heine Securities. In 1994, he “cut his teeth” in making a run on Michigan National, which then was sold the same year to an Australian bank. In early 1995, Michael Price, together with his top analyst Ray Garea, met with Tom Labreque (then Chase Manhattan Chairman and CEO) to discuss Chase's business strategy. Shortly thereafter, Michael Price concluded to make a run for Chase and not much later his firm Heine Securities announced that they had purchased over 6% of Chase’s common stock, thus becoming a significant shareholder.

This propelled Chase's Board to request management to act in the interest of shareholder value. One option was to find a merger partner. During that tense period, Citi and BoA did not seem to make much sense as a merger partner. They had the same or even greater problems than Chase. A combination with either of those two would probably also run into regulatory as well as political problems, because of the significant amount of overlapping businesses, eliminating competition, as well as the huge job cuts that would ensue.

Chemical had fewer non-performing loans, plus they had built up a good size U.S. Investment Banking operation, generating trading and fee income primarily from its middle market customer base. That fact was well recognized by Wall Street. This led Chase, which still had a sizable international franchise, and Chemical to consider a merger seriously. Tom Labreque, who sadly died only a few years later (in 2000) then led Chase's negotiation with Chemical to a “merger of equals”. The rest is history.

From Sergei Boboshko (1/25/21): I have been following some of the responses to Don Layton’s interesting piece on the Chase/Chemical merger/acquisition, which was a significant event to most of us, regardless of which bank we came from. My own recollections of that time focus more on the ‘cultural’ implications and ramifications that colored that event, rather than on which bank ‘won’.

From Sergei Boboshko (1/25/21): I have been following some of the responses to Don Layton’s interesting piece on the Chase/Chemical merger/acquisition, which was a significant event to most of us, regardless of which bank we came from. My own recollections of that time focus more on the ‘cultural’ implications and ramifications that colored that event, rather than on which bank ‘won’.I joined Chase on St Paddy’s Day in 1969 as a ‘credit correspondent’, which position was responsible primarily for responding to credit inquiries on our clients by other banks or creditors. By August 1971, and after a stint in the Loan Review Division, I was accepted into the Global Credit Training Program on the 7th floor at 1CMP. Immediately after completing training in October 1972, I spent the next nine years as a lending officer on overseas assignments. Thereafter I spent the next 13 years in New York, primarily in the Middle Market Banking Group, during which I also spent 2 ½ years as a work-out officer in the Special Loan Group under Margaret Klein. My training and experience was thus very deep as a line lending officer and manager of client relationships.

During my later years, Chase was progressively more and more interested in adding investment banking services to our product offerings, and I recall attending many such training seminars to supplement my skills as a corporate/commercial lender.

By the time of the Chase/Chemical merger/acquisition in 1995, I was back overseas, this time as Senior Country Officer and President of Chase Manhattan Bank International, our new Russian banking subsidiary, which we had just established to replace the Chase Representative Office, which dated back to 1973.

I was SCO in Russia for 4 ½ years (June 1994 – December 1998), during which we were very successful, and during which I began to experience the cultural shifts that I am sure many of us observed and are the subject of this piece. With the benefit of hindsight, I now understand that these cultural shifts were due not only to the merger/acquisition, but also to the new bank’s desire to become a major investment bank, consistent with global banking trends at the time.

For me, the fundamental cultural shift that occurred was the new bank’s emphasis on products rather than on relationships. As a proud Chase man, I was steeped in the tradition that emphasized the development and management of client relationships. The importance of products, however, was now being emphasized over client relationships, with the introduction of ‘matrix management’ as our new mode of operation.

Our primary lines of business/products at that time at Chase Moscow were corporate lending, trade finance, securities trading, global custody and financial institutions. Under matrix management, and with the exception of corporate lending (which reported directly to me), each such line of business/product had a ‘solid line’ reporting to a product manager (usually in London or New York), with a ‘dotted line’ reporting to me as SCO. The inevitable result of this, and despite how it was described on paper, was the gradual reduction in the role and authority of the SCO. In previous years it had been unheard of, for instance, for a Chase colleague from outside the country to call on an existing or prospective client unaccompanied by an officer from the local Chase entity, or even worse without the knowledge and approval of the SCO. As this began to occur I recall complaining not only to European management but to senior management in New York. My recollection is that I heard a lot of sympathy, but nothing changed.

There were a number of other examples of this narrower emphasis on product over relationship with which I was uncomfortable, most notably as regards the credit process. Coming from a background where stringent credit risk analysis was integral to our Chase culture, I was very disturbed that our product specialists relied more on third-party credit rating agencies than on our own analysis. I understood that buyers of those securities would rely on the credit agencies, but were the rating agencies now replacing our own credit process?

Perhaps these cultural changes were inevitable due to the growing emphasis on investment banking, rather than solely due to the merger/acquisition. Perhaps my discomfort was due to the emphasis on new skills that were difficult for someone coming from the ‘old’ Chase culture to absorb. I left Chase at the end of 1998 and I am pretty sure that I would not have survived the acquisition of JPMorgan in 2000 had I stayed on. Nevertheless, I have no regrets.

I worked for Chase for almost 30 years, which represented the greater part of my professional life. This association was responsible for the training and preparation for a most rewarding life and career, affording me and my family opportunities that we would otherwise not have had.

It has now been 22 years since I left Chase and I thus do not know what sort of culture permeates JPMorgan Chase today. What I do know is that it is a global financial powerhouse easily eclipsing any of its ‘heritage’ banks.

From Clare Johannessen (1/14/21): I started my career at Chase in 1975 in a technology training program and was placed in Money Transfer technology at the end of the program. I worked there in various capacities, (eventually becoming a VP. I felt I had seen it all in my role, and then Chase merged with Chemical in 1996. I have to say I was terrified and was convinced I would lose my job, Bubt I was fortunate and did not. Instead, I (and many others from heritage Manny Hanny, Chemical and Chase) worked our “you know what’s off” to pull off an extremely successful merger. We participated in creating “the best of the best”. This level of work and pride created bonds that we maintain till this day.

From Clare Johannessen (1/14/21): I started my career at Chase in 1975 in a technology training program and was placed in Money Transfer technology at the end of the program. I worked there in various capacities, (eventually becoming a VP. I felt I had seen it all in my role, and then Chase merged with Chemical in 1996. I have to say I was terrified and was convinced I would lose my job, Bubt I was fortunate and did not. Instead, I (and many others from heritage Manny Hanny, Chemical and Chase) worked our “you know what’s off” to pull off an extremely successful merger. We participated in creating “the best of the best”. This level of work and pride created bonds that we maintain till this day.

I stayed in Money Transfer (then part of Treasury and Security Services), and continued to be involved in all the subsequent mergers until the end of 2007. With each merger, our original Chase/Chem merger team grew larger–adding participants from the other banks. The attitudes of these various merger teams was never who bought who OR what management team was in charge, it was just “Get It Done” (on time and with quality-of course!).

For me personally, I loved the mergers, as I learned so much with each merger and gained so many friends. Today, when I look back, I have a feeling of enormous pride for helping to create the world class bank we have today. My opinion is that all alumni contributed to this regardless of their role in the various mergers or their heritage bank.

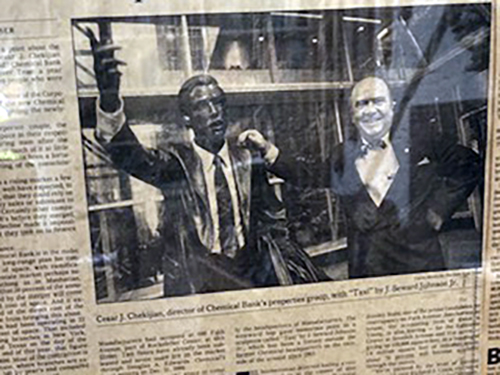

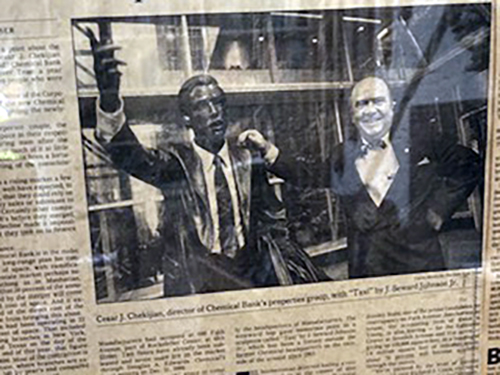

From Cesar J. Chekijian (1/9/21): In the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, I was Senior Vice President and head of Corporate Real Estate for Manufacturers Hanover Corporation. One day in the Spring of 1991, I was having lunch with a close friend of mine at the Executive Dining Room at 50/270, when he confided in me that through his father-in-law, who was Board Director of Chemical Bank, he had learned that the Chairman of Chemical Bank had met with Paul Volker, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve, for clearance to take over Manufacturers Hanover...and that Mr. Volker had said that Chemical Bank was not in a position to do such a thing. This is when leading banks were all in an upheaval due to the default of sovereign loans by Lesser Developed Countries.

From Cesar J. Chekijian (1/9/21): In the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, I was Senior Vice President and head of Corporate Real Estate for Manufacturers Hanover Corporation. One day in the Spring of 1991, I was having lunch with a close friend of mine at the Executive Dining Room at 50/270, when he confided in me that through his father-in-law, who was Board Director of Chemical Bank, he had learned that the Chairman of Chemical Bank had met with Paul Volker, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve, for clearance to take over Manufacturers Hanover...and that Mr. Volker had said that Chemical Bank was not in a position to do such a thing. This is when leading banks were all in an upheaval due to the default of sovereign loans by Lesser Developed Countries.

I passed the information immediately on to our Chairman, who, without hesitation, the same afternoon, had walked across Park Avenue to Chemical Bank's HQ at 277 Park, without an appointment. The two Chairmen had met, apparently with a short discussion on successive succession, and they agreed on a "Merger of Equals". And that is how the "Domino Effect" of multiple mergers started.

Following the announcement of the merger, The New York Times published an article, with a picture (above) of me and the statue of a man calling a cab, which was in front of 277 Park, seeming to be pointing across the avenue to 270 Park, implying (according to NYT) that it was beckoning to Manufacturers Hanover all along!

From Michael Prasad (12/6/20): I would like to respond to Don Layton’s piece “The Merger Name Game” from a slightly different perspective – one of someone on the losing side of all these mergers. (Those five years between 1995 and 2000 went by for me like a blur). While I see that the Chase Alumni Association is attempting to assimilate in the ManHan (in reality, we all pronounced it MannyHanny), Chemical and (maybe even the) JPMorgan folks, there was a very different corporate culture among these four organizations during those years.

From Michael Prasad (12/6/20): I would like to respond to Don Layton’s piece “The Merger Name Game” from a slightly different perspective – one of someone on the losing side of all these mergers. (Those five years between 1995 and 2000 went by for me like a blur). While I see that the Chase Alumni Association is attempting to assimilate in the ManHan (in reality, we all pronounced it MannyHanny), Chemical and (maybe even the) JPMorgan folks, there was a very different corporate culture among these four organizations during those years.

And I feel no loyalty or pay no fealty to any of them, except for Chase.

Mr. Layton may speak in terms of stock prices and net asset values, but when he describes the “assets go home every night”, he is really speaking of the sales people – the relationship managers and those who can move and then take their clients (and revenue) to another firm. Given this is an important factor in the commercial banking and financial services business, he also speaks to cost cutting – and that means the vast majority of people who work at the banks – not just buildings and systems, but people - whose jobs and livelihoods are parts of a corporate headquarters calculation on how they themselves can keep hold of their own jobs.

I started as an intern at Chase in 1986, got hired full time as a programmer in Corporate Controllers in 1987. I think that same year we had financial troubles, switched our pension plan to a 401k, did an early retirement program, hiring freeze, etc.–the kind of steps most companies do when they think of their own workforce as a critical component to staying in business. When you see that you have too many branches in New York City, first thing you should do is look at consolidating the real estate, but smart businesses also think about how they will keep their workforce by retraining some tellers to be programmers, for example. And you also slow down nationwide expansion. When things get better, then you look for acquisitions (which we did with banks in Ohio, Texas and California, etc.).

Right before the Chemical merger with Chase, we saw how MannyHanny was swallowed up by Chemical. It was gone. MannyHanny didn’t have the cache of Chase or JP Morgan or Bank of New York – nor the rich history in the New York Banking world. (They sponsored the NYC Marathon for a few years, that’s what I recall about MannyHanny.) Remember, we had the wooden water pipes and the dueling pistols between Hamilton and Burr. We were the Rockefeller bank. I remember all those the years with great fondness, up until the point when we merged with Chemical. The “old” Chase had Vision and Values, Total Quality Management (TQM) and Excalibur. The “new” Chase was just the name on the door, soon to be run by others. Slash and burn.

Then the Chemical folks came in, took over and broke up all our teams. I got lucky (for a few years at least) and moved over from Corporate Controllers to Private Banking – one of the few enclaves of the former Chase senior leadership still standing, in many ways because of Mr. Layton’s adage that the “assets that go home every night”: Chemical did not have as strong of a Private Bank as Chase did. The culture was still very different with the merged organizations. I worked for a Managing Director who was former MannyHanny; everyone was bringing their own corporate history baggage and biases. For me, I saw less teamwork and more me-work from colleagues. I don’t even remember any holiday parties from those merged years – not like the ones at the top of Chase Plaza with those giant shrimp!

With JP Morgan, it was all sales all the time (not quite Glengarry Glen Ross, but sometimes it did felt like that) – calculating the merger cost-savings numbers and sales, sales, sales. I was moved over to a Relationship Management position after working the Euro conversion and Y2K (not to mention the successful rollout of the World MasterCard and other product launches). I got lucky (once again) to get my Series 7 and 63 licenses (a requirement of Morgan for their Relationship Managers), but, candidly, I am not a Salesperson. Again, more me-work not Teamwork. Ever try building a book of business from scratch – especially if you have no Loan Officer training? I think I was already on the chopping block when 9/11 came and my bosses waited a month before letting me go. When my own asset went home on October 11, 2001 for the last time, I left with six banker boxes in a livery cab.

There’s certainly more to my career story (for another time, maybe), but what I remember most is the people I worked with at Chase between 1986 and 1998. Ask me how much the bank made in any of those years or what our credit rating was, and I would have to look it up. Ask me to tell you a story about how one of my friends and compadres made a difference in the organization they really cared about, and you will be listening to me for quite some time. Mr. Layton certainly had more significant issues (and rightfully so, given his level of priorities and responsibilities) to deal with during these mergers – including the reality that without some massive changes and cuts, the very survival of our enterprise was in jeopardy – yet, in my opinion, that’s not all there is to the story of the “Merger Name Game”. For many of us, the reality of finding a new job in a post-9/11 economy (and not get the grandfather clock and post-25-year retirement of our predecessors) was our new found responsibility to ourselves and our families – and one where we would never find that Chase teamwork again.

From

Ed Moran (12/17/20):

I read Don Layton’s story of the naming of the present day JPMorgan Chase with interest and Michael Prasad’s response to it. I have a couple of comments on both.

Michael refers with some pride to the fact that “we had the wooden water pipes and the dueling pistols…the Rockefeller bank.” Actually, Michael “we” had both from the Bank of Manhattan archives not from the Rockefeller side. The water pipes were examples of how The Bank of the Manhattan Co. got it start. The pipes were installed as the way to carry water to the newly developing parts of lower NYC. The Manhattan Water Company was so “liquid” from its new water system that it started a bank. At least one, if not both of the pistols were purchased by that bank in the 1930s as an appropriate reminder that the bank itself was founded by Aaron Burr.

I started my checkered career at the Chase Manhattan Bank in the mid-1950s, working three summers as a clerk and a messenger. I got those jobs through the intercession of my uncle, Joseph J Moran who was the head of the International Department at The Bank of the Manhattan Company before the merger in 1955. I use the full title of that bank because my uncle insisted that I always do so. He was adamant that it was the bank of the water company and should be referred to in that manner. Uncle Joe had come up the ranks in the foreign exchange area and was a bit of a stickler for accuracy. Which brings me to my response to Don Layton’s piece. Uncle Joe was equally adamant about the fact that a requirement of the Chase National/Manhattan merger was that the Manhattan name always be part of the bank’s title. If true, that requirement seems to have gotten lost in the merger name game. Or maybe Uncle Joe was just reminiscing. He never did like the merger and retired a year or two after it occurred. In that respect, he and Michael Prasad had much in common.

Response from Mike Prasad (12/29/20): Dear Ed Moran and others at the Chase Alumni Association,

A mea culpa from me – I am guilty of the “assimilation” mindset that I was admonishing others with a false sense of superiority. For me, the “Manhattan” side of the Bank which came in 1955 (and the Equitable Trust Company merger before then in 1930) were already baked in to the culture of Chase. I still stand by my position that the JPMorgan Chase bank of today is very different (and not always in a good way for its back office workforce) than the Chase Manhattan Bank I was a part of between 1986 and 2001. Winners get to write the history books, as they say.

Again, my apologies to Mr. Moran – his is a name I recall from annual reports and senior management briefings. My diatribe was quickly written and without the full research I should have made. Jimmy Koo, Doug Cioffi, Jeanne Warner, Lester Stephens, Mike Esposito, Tom Labrecque – I used to count how many spots I was from the top. I take the view that many of the titans of the U.S. banking industry helped build this country – both entities and individuals. Chase, National City Bank and the Bank of New York certainly count amongst those. As do historic names like John Thompson and Winthrop Aldrich. I am also remiss in recalling that my father – a college professor who loved writing and research – published a piece in 1999 on the early years of both the Citi and Chase – and he mentioned both the Bank of Manhattan and Equitable Trust. In fact, I even helped him meet with the Chase archive folks to do his research. The article he published is stored up in a box in our attic – but I was able to find a copy online at https://thebhc.org/sites/default/files/beh/BEHprint/v028n2/p0201-p0212.pdf.

Happy New Year to all!

Response from Ed Moran (12/29/20): Mea Culpa not needed. I sympathize with Michael. Change is often painful as I know the various mergers were. I joined the bank after my five years in the AF precisely because of the people and the spirit I had experienced in my summers working there as a callow youth. Banking, to be successful, requires teamwork and working as closely together as we often did, breeds real friendships. It’s tough when those teams break up as the companies combine and the more wedded you are to the unit, the more you fear that these changes will not be for the best. And some times…they really aren’t.

From Caroline "CJ" Smith: I have been surprised to hear, once again in Alumni Association missives, of the Chase/Chemical merger being characterized as the purchase of Chase Manhattan Bank by Chemical Bank. At the time, I was no longer working at the banks, but was a fixed income financial analyst on Wall Street.

My understanding is that it may be more representative to say that Chase bought Chemical at the holding company level. Meanwhile some confusion may arise since Chase Manhattan Bank, the acquiring operating bank, merged into the legal bank entity of target Chemical Bank. This took place because of a regulatory arbitrage strategy. Chemical Bank, the operating bank, was a New York State Bank and not subject to national bank supervision by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency*. State regulation was deemed less invasive and less stringent. Thus the Chemical Bank legal entity persisted.

I haven’t looked back at the management transition at the time, but I will surmise that the C-suite that remained was largely Chase in their experience. This also points to the purchase having been by Chase of Chemical.

Thank you and I am happy to discuss this further.

* Ms. Smith served as a Risk Specialist at Office of the Comptroller of the Currency from 2005 to 2016.

Reply from Don Layton: In practical and people terms, the transaction was a purchase of Chase by the new Chemical: the CEO of Chemical stayed as the ongoing CEO of the combined company, the CEO of Chase (Tom Labrecque) was not promised CEO (and indeed retired without becoming it); culturally, as I stated, it was pursued more as a merger-of-equals (best of both) than a classic take-over. The writer's "surmise" that the C-suite was largely Chase in their experience is completely inaccurate. Top management was, in the best-of-both manner, a mix of executives from the two companies, but with Chemical having the upper hand via the CEO position; after things shook out over the next several years, top management did become somewhat more Chemical-dominated (supplemented by key outside hires), with few from heritage Chase.

In technical legal terms, i.e. which corporate or bank charters survived, that was handled by lawyers, and I do not even recall which did, as it was of so little impact.

From Ken Jablon: On the Consumer side of the merged bank, the lending services went to Chase executives and the branch, and deposit services went to Chemical executives (mostly heritage Manny Hanny individuals). I am not familiar with what happened on the wholesale part of the merged bank.

From Ron Mayer (attorney in Chase's Legal Department at time of the merger): Both Chemical Banking Corporation and Chemical Bank were the surviving legal entities in the merger–a legal point without much significance.

While saying that Chemical bought Chase (which I often do) is an overstatement, it does reflect the fact that Chemical was the dominant party. Shipley was chairman. Chemical insiders had three directors (Shipley, Harrison, Miller), Chase had two (Labrecque and Kruse). Most importantly, Chemical management knew what it was doing with organizing a merger. They created the various systems that controlled the merger process, while we Chase folks just looked on.

When the Chase pension plan was eliminated in the late 1980s it was replaced with a defined contribution plan, not a 401k.

ome time before the merger, I remember weekly meetings to make changes to the branch bank account offerings. Don Boudreau, who ran the Retail Bank, sat at the head of the table and I sat at the foot on the table. On one side were the marketing folks and on the other side were the systems people. Each week the marketing folks would describe the ideal account offerings. Each following week the systems folks would describe how these changes could be implemented, and the marketing folks would say that was not exactly what they intended. Then the cycle would repeat. My recollection was that when the project was over, the resulting account offerings looked suspiciously like those of Chemical Bank.

ome time before the merger, I remember weekly meetings to make changes to the branch bank account offerings. Don Boudreau, who ran the Retail Bank, sat at the head of the table and I sat at the foot on the table. On one side were the marketing folks and on the other side were the systems people. Each week the marketing folks would describe the ideal account offerings. Each following week the systems folks would describe how these changes could be implemented, and the marketing folks would say that was not exactly what they intended. Then the cycle would repeat. My recollection was that when the project was over, the resulting account offerings looked suspiciously like those of Chemical Bank. From Karl Schmidt (2/6/21): I worked at Chase from 1966 to 1996, mostly at the Corporate Finance Department at Head Office. As best as I could, I have also looked at Chase from an investor’s point of view related to my 401(k) plan.

From Karl Schmidt (2/6/21): I worked at Chase from 1966 to 1996, mostly at the Corporate Finance Department at Head Office. As best as I could, I have also looked at Chase from an investor’s point of view related to my 401(k) plan.  From Sergei Boboshko (1/25/21): I have been following some of the responses to Don Layton’s interesting piece on the Chase/Chemical merger/acquisition, which was a significant event to most of us, regardless of which bank we came from. My own recollections of that time focus more on the ‘cultural’ implications and ramifications that colored that event, rather than on which bank ‘won’.

From Sergei Boboshko (1/25/21): I have been following some of the responses to Don Layton’s interesting piece on the Chase/Chemical merger/acquisition, which was a significant event to most of us, regardless of which bank we came from. My own recollections of that time focus more on the ‘cultural’ implications and ramifications that colored that event, rather than on which bank ‘won’. From Clare Johannessen (1/14/21): I started my career at Chase in 1975 in a technology training program and was placed in Money Transfer technology at the end of the program. I worked there in various capacities, (eventually becoming a VP. I felt I had seen it all in my role, and then Chase merged with Chemical in 1996. I have to say I was terrified and was convinced I would lose my job, Bubt I was fortunate and did not. Instead, I (and many others from heritage Manny Hanny, Chemical and Chase) worked our “you know what’s off” to pull off an extremely successful merger. We participated in creating “the best of the best”. This level of work and pride created bonds that we maintain till this day.

From Clare Johannessen (1/14/21): I started my career at Chase in 1975 in a technology training program and was placed in Money Transfer technology at the end of the program. I worked there in various capacities, (eventually becoming a VP. I felt I had seen it all in my role, and then Chase merged with Chemical in 1996. I have to say I was terrified and was convinced I would lose my job, Bubt I was fortunate and did not. Instead, I (and many others from heritage Manny Hanny, Chemical and Chase) worked our “you know what’s off” to pull off an extremely successful merger. We participated in creating “the best of the best”. This level of work and pride created bonds that we maintain till this day.  From Cesar J. Chekijian (1/9/21): In the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, I was Senior Vice President and head of Corporate Real Estate for Manufacturers Hanover Corporation. One day in the Spring of 1991, I was having lunch with a close friend of mine at the Executive Dining Room at 50/270, when he confided in me that through his father-in-law, who was Board Director of Chemical Bank, he had learned that the Chairman of Chemical Bank had met with Paul Volker, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve, for clearance to take over Manufacturers Hanover...and that Mr. Volker had said that Chemical Bank was not in a position to do such a thing. This is when leading banks were all in an upheaval due to the default of sovereign loans by Lesser Developed Countries.

From Cesar J. Chekijian (1/9/21): In the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, I was Senior Vice President and head of Corporate Real Estate for Manufacturers Hanover Corporation. One day in the Spring of 1991, I was having lunch with a close friend of mine at the Executive Dining Room at 50/270, when he confided in me that through his father-in-law, who was Board Director of Chemical Bank, he had learned that the Chairman of Chemical Bank had met with Paul Volker, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve, for clearance to take over Manufacturers Hanover...and that Mr. Volker had said that Chemical Bank was not in a position to do such a thing. This is when leading banks were all in an upheaval due to the default of sovereign loans by Lesser Developed Countries.  From Michael Prasad (12/6/20): I would like to respond to Don Layton’s piece “The Merger Name Game” from a slightly different perspective – one of someone on the losing side of all these mergers. (Those five years between 1995 and 2000 went by for me like a blur). While I see that the Chase Alumni Association is attempting to assimilate in the ManHan (in reality, we all pronounced it MannyHanny), Chemical and (maybe even the) JPMorgan folks, there was a very different corporate culture among these four organizations during those years.

From Michael Prasad (12/6/20): I would like to respond to Don Layton’s piece “The Merger Name Game” from a slightly different perspective – one of someone on the losing side of all these mergers. (Those five years between 1995 and 2000 went by for me like a blur). While I see that the Chase Alumni Association is attempting to assimilate in the ManHan (in reality, we all pronounced it MannyHanny), Chemical and (maybe even the) JPMorgan folks, there was a very different corporate culture among these four organizations during those years. From Ed Moran (12/17/20): I read Don Layton’s story of the naming of the present day JPMorgan Chase with interest and Michael Prasad’s response to it. I have a couple of comments on both.

From Ed Moran (12/17/20): I read Don Layton’s story of the naming of the present day JPMorgan Chase with interest and Michael Prasad’s response to it. I have a couple of comments on both.