How Chase Responded on 9/11

(Crisis Mode, and the Untold Story of the Diesel Fuel)

With special thanks to Ralph Aiello for suggesting this story.

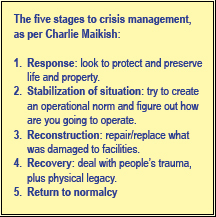

“The World Trade Center was my life for 27 years,” said Charlie Maikish (photo left), who, working for the Port Authority, had helped build, develop and manage its towers. He was in charge there in February 1993 when a terrorist bombing in the Center’s underground garage killed six and injured thousands.

“The World Trade Center was my life for 27 years,” said Charlie Maikish (photo left), who, working for the Port Authority, had helped build, develop and manage its towers. He was in charge there in February 1993 when a terrorist bombing in the Center’s underground garage killed six and injured thousands.

But on September 11, 2001, he was head of real estate for JPMorgan Chase, whose 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza (1CMP) was a 12-minute walk from Ground Zero.

“Nobody knows that facility (WTC) better than I do,” Maikish told Bill Harrison, then JPMC’s president and CEO, who was stuck in Brooklyn with John Farrell, JPMC’s human resources head, when the planes struck.

“Bill made it clear to me: ‘You work for Chase now,’” Maikish recalled, and he had plenty to do.

That first day, Maikish recalled recently, the Bank went into crisis mode from 270 Park Avenue, activating a crisis line and crisis plan, with senior management stepping aside.

“We started with hourly conference calls on a bridge to check on the state of business,” he said. “Cell phones were out, but landlines were still operating. We had a call-in number, and each of the corporate functions would call in on the hour and report what would happen. Harrison and Farrell finally got in from Brooklyn and set up a war room in Farrell’s office.”

Seeing how the implosion of the Towers was effecting the foundation of adjacent buildings, the Army Corps of Engineers was calling for an evacuation of 1CMP.

“You don’t evacuate into peril,” said Maikish, who with Farrell, called for a lockdown at 1CMP. They didn’t want their people going into harm’s way. Eventually they let out some employees, keeping security and facilities management, as well as the trading desk.

“We recirculated all the air in 1CMP and supplemented with filtered outside air. We told the head of branches to let people know to shelter in place until we could stabilize, assess and get out of there safely. We set up a triage in one of the branch banks at 1CMP, where we could send hysterical employees and calm them down.”

Ralph Aiello, who worked for Farrell and represented him on the crisis calls until Farrell could return from Brooklyn, noted that 1CMP had a medical department, many nurses and enough cots that “we could set up for 2,000 people if we had to”. Aiello said that guards at 1CMP were pulling people in need off the street, bringing them into the lobby whether they were employees or not. Some had been hit by flying debris, some had been overwhelmed by smoke.

Chase had a couple of retail branches in the lower floors of the World Trade Center. Aiello said everyone got out. (We're saving the story of what happened to the contents of the vaults for another time.)

Chase had a couple of retail branches in the lower floors of the World Trade Center. Aiello said everyone got out. (We're saving the story of what happened to the contents of the vaults for another time.)

Meanwhile, Harrison, Farrell and Maikish, working at Park Avenue and 47th Street, decided they had to go downtown to see firsthand what the state of affairs was. “We needed to see what had to be addressed, in HR, tech, clients, life, safety, by function and region,” Maikish said. “We kept track of follow-ups for the next meeting—what needed to be done within the hour. Our goal was to recover for Chase both its people and the business.”

“That night I contacted people I knew downtown, including Michael Regan, who was first deputy commissioner for the New York Fire Department and had also worked at the World Trade Center. I told him that we needed to go downtown and survey where we were at 1CMP, but everything was locked down south of Canal Street.

Having gotten permission to go south of Canal, Maikish, Farrell and Harrison went downtown that first night, first looking at Ground Zero. “The heat of compression had turned everything to ash,” Maikish recalled. “Then we got over to 1CMP. Six inches of dust was on the streets. We learned that the dust cloud had hit MetroTech in Brooklyn.”

For employees who couldn’t get home from Manhattan, JPMC set up housing at 270 Park – which was 100 percent functional – and at 1CMP, in the cafeteria and temporary facilities.

“Communications was the only thing we needed to improvise. Quite importantly, we kept the data centers open, live and functioning (see sidebar story),” Maikish said. “We brought in pizzas in cleaning vans.”

It took 10 to 14 days for 1CMP to reopen for most employees. Maikish said the object was “not to get to full, but at least 60 percent”.

“We wanted to tell people it was safe structurally and environmentally and security-wise to come back,” Maikish said. Fans were fouled by dust. The Bank conducted extensive air monitoring. Plants had died, and the space needed new landscaping. Miraculously, the famous 1CMP/Chase art collection had not been damaged.

Given that the pile at Ground Zero was still smoking for six to eight months, some 1CMP employees refused to come back.

Maikish advised Harrison that they set up a welcome back program, as he had done at the WTC after the 1993 bombing.

“When we bring people back,” Maikish told his boss, “there have to be flowers in the lobby, and it has to be sparkling, with senior management there as well.” Ther3e were special coffee mugs – as well as psychologists and medical staff at the ready.

“I remember one woman saw Bill and fell into his arms and started crying,” Maikish said, 18 years after the event.

A few days later, Harrison led a Town Hall. Maikish had advised, “You have to tell these people they were heroes to come back and dedicate themselves back to Chase.”

“Bill praised the ingenuity of Chase employees. They gave him standing ovation, because he was the chairman and CEO, and people were committed to Chase, because Chase was committed to them,” Maikish recalled. “John Farrell was a big part of that – understanding the importance of preserving intellectual capital.”

And JPMC was particularly generous to a competitor: Having an almost full building vacant on Broad Street following the JPMorgan merger, JPMC made it available to the Bank of New York, displaced from its. on 9/11.

And JPMC was particularly generous to a competitor: Having an almost full building vacant on Broad Street following the JPMorgan merger, JPMC made it available to the Bank of New York, displaced from its. on 9/11.

The return to normal included a new definition of what was going to be normal, Maikish said. Now there were barriers outside, turnstiles and emergency lighting. Mike Regan was hired as head of security and life safety. (Note: Regan is now Vice Chairman in the Global Real Estate Department at JPMC). Fire drills became evacuation drills, and drills became simulations of terrorist attacks.

Maikish, who went on to help rebuild Lower Manhattan, said one could continue looking right down at the pile at Ground Zero from 1 CMP.

As for 9/11, Maikish said he relives it all the time. “I thought of the WTC as ‘my twins’. I built them, defended them, ran them and recovered them, I lost a lot of people I knew.” He went to more than 100 funerals until he couldn’t any more.

“Chase was really good. I didn’t go home for a month. They put me up in the Waldorf, got me clothes. (His children, in suburban New York, were 14, 16 and 18 at the time and didn’t see much of him.)

“I tried to get on with living life differently,” he said. “I had an apartment down there on 9/11, gave it up and moved to midtown...

“You try to suppress it, but anniversaries bring it back. At the 9/11 Memorial Museum, it’s startling when you see what it’s all about. Part of what drives me is the need to preserve our NY-NJ regional way of life, to protect our social institutions and not to alter a free and democratic society.”

The Untold Story of the Diesel Fuel

(as told by Charlie Maikish)

Unlike the other major financial powerhouses in Lower Manhattan on 9/11, JPMorgan Chase had a backup diesel-powered generator. As Charlie Maikish recalls:

“We had backup data centers in Delaware, Carlstadt, NJ, and Ohio, but not real-time data services. Our real-time services were at 1CMP, and we had diesel generators. The Fed asked for our help. The Bank of NY was out of business, and Barclays and Deutsche Bank’s operations were going...

"We were clearing for everyone up to midnight, and then Feds covering after midnight.

"By the first night, we were running very low on fuel for the trading floors and data center, and nothing could come south of Canal Street. I called Mike Regan, first deputy fire commissioner, who told me, 'You‘re not going to get (Mayor) Giuliani’s attention.'

“I spoke with Gene McGrath, head of ConEd, who told me, 'We’re functioning off of rubber bands and spits – I’ve got lines in such condition that it better not snow. We’re going to have to replace this over time. The power system will be unstable for at least another year.'

“Meanwhile, I realize that if you get a glitch for 10 seconds on the trading floor, millions of dollars can be lost.

“The diesel fuel depots were in Queens. Could we get the fuel over the Brooklyn or Manhattan Bridges? I explained this to Joe Lhota, the deputy mayor. ‘We need the fuel. You’ve got to get to the mayor. This is the world economy you’re talking about’, and Lhota said, ‘You’re not going to get his attention. Do what you have to do.’

“And so I told Eddie O’Shea, who was in charge of operations/facilities management, to do what he had to do. He went to Queens and got the fuel depot to put diesel on some flatbeds. Then Eddie got two black Suburbans and put red lights on them, and the black Suburbans accompanied the flatbeds across the Brooklyn Bridge. The National Guard, thinking it was a police convoy, just waved them across.

“I had told Mike Regan, so we could tell the Guard he knew if the trucks were stopped, but they just rode across the bridge.”

_____________________________________

Please send comments and your 9/11 stories to news@chasealum.org. We have run remembrances in the past.