Josse Borremans:

Charles Michael de Wolf & Certificate 114

"Or which Chase subsidiary lay the foundation for the United States to become a prime credit risk?"

Josse Borremans gave a version of this presentation at the third reunion of the Belgian CAA chapter, held in Antwerp on March 29, 2019.

Josse Borremans gave a version of this presentation at the third reunion of the Belgian CAA chapter, held in Antwerp on March 29, 2019.

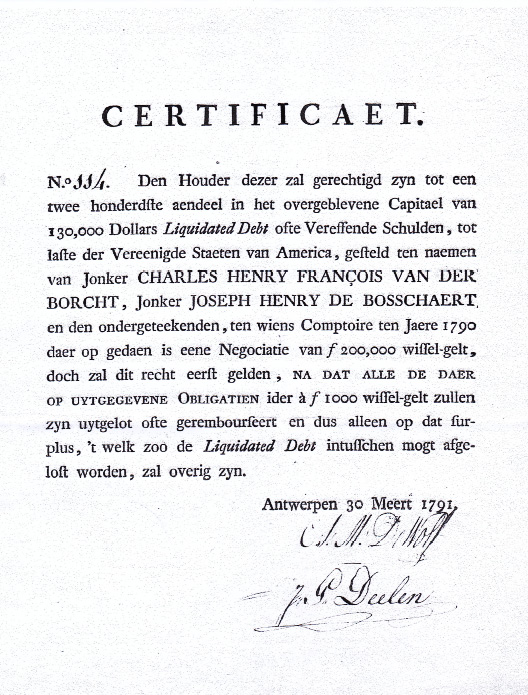

Finding the founding father of the bank

A year ago, I bought a document labelled Certificate 114 in an auction in Brussels. It is a document issued on March 30th, 1791 in Antwerp, then located in the Duchy of Brabant (now part of the Kingdom of Belgium). It is signed by Charles Michael De Wolf (1747-1806), a local banker, in favor of two members of the lower nobility who paid 1000 Guilders of Brabant in exchange for a participation of USD 630 plus interests of liquidated debt due by the United States of America.

Obviously, the document raises many questions, some of which I will attempt to answer.

Who was Charles Michael De Wolf?

De Wolf was a banker in the City of Antwerp. At the time of his birth (1747), the city was in the Duchy of Brabant, then owned by the Habsburg Dynasty. During De Wolf's lifetime, Brabant was annexed by France as part of the French Republic that, under Napoleon Bonaparte, became the French Empire. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo (1815), Brabant became part of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands. In 1830 it was integrated into the Kingdom of Belgium–a lot of mergers and splits territorially speaking.

De Wolf was not predestined to become a banker, as banking was, at that time, an elite profession. He was born into a simple middle-class family with some property, but by no means a wealthy family. His father was a glassmaker. The family owned two houses and a shop. Michael was their only child. His parents sold a house and mortgaged the other one to pay for their son’s education, which was a success as, at the age of 20, Michael entered the “civil service” and five years later was named an official for Antwerp, being appointed as the tax collector for the greater Antwerp region.

Under the ancien régime, the tax collector function didn’t come with a fixed salary. The official/tax collector received a fee on the amount of the taxes collected. The main source of his income, however, had to come from investing the float of the tax money. As failure to remit the taxes collected to the Government was deemed a criminal offence and subject to severe punishment, De Wolf’s appetite for risk had to be very limited. Sounds familiar.

Fortunately for him, the bank he hadn’t set up yet would be acquired 200 years later by Chase, and that offered possibilities to solve his risk problem in a mysterious way. Indeed, what I remember of financial engineering and investment banking is that the best results are achieved when the laws of physics and considerations of time and space are ignored.

The instructors of Chase’s AFRA seminars would have analyzed De Wolf’s situation as follows: "Michael, your situation is that you are structurally long on cash and short on high quality income-generating assets. You have to look for counterparties who are in the opposite situation, short on cash and long on income-generating assets. Then the logical thing to do is to enter into a swap arrangement with that counterparty and swap cash on a temporary basis for interest and fee income, holding the assets as a guarantee.

Enlighted by the modern theory of financial engineering, that is exactly what De Wolf did as illustrated by his arrangement with Prince de Mérode as follows. The Prince was fabulously wealthy. He owned 37 estates spread over Western Europe that generated considerable income, and yet he was regularly short of cash, the reason being that Prince de Mérode was the colonel-proprietor of a cavalry regiment and had to cover all the expenses of this unit out of his own pocket. So, De Wolf lent him 400,000 guilders at 6% interest plus upfront fees of 5%. He secured his loan with a first-rank mortgage on de Mérode’s estates in the Duchy of Brabant. In the summertime, after the harvest, there was an annual reimbursement.

De Wolf gradually developed an important private banking business from the lending side, even internationally. His largest loan (1,800,000 Guilders of Brabant) was granted in 1791 to Prince Frederic, Duke of York (1763-1827), George III ‘s second son. The Duke was the commander-in-chief of the army of the First Coalition that invaded France. De Wolf’s excellence as a banker was demonstrated by the fact that although the side he financed lost, the loan to the Duke of York was fully repaid thanks to good tangible securities. Under Chase’s credit policy rules, this transaction would have required the consent of the Bank’s President.

By now you may have sensed that under the ancien régime, the differences between a tax collector and a banker were rather fluid, and yet there is a precise moment at which De Wolf gets rid of the ambiguity and chooses to become a banker. De Wolf could live very comfortably as a tax collector ; taxes collected provided a natural funding for his financing. To become a banker, he needed a substantial capital base, which he lacked, but sometimes opportunity knocks, even for a banker.

Opportunity knocks

Indeed it did, and for De Wolf and many others that was indirectly the victory of the Americans in their War of Independence against Britain. Following the capitulation at Yorktown, the British were in a very bad mood, and the Royal Navy took to bullying merchant ships of most other nations on the high seas. This had a negative effect on the bilateral trade between the colonies in the Americas – including the now independent USA – and Europe. The consequences were huge: Colonial goods could not be sold in Europe, and European goods could not be exported to the colonies and the USA.

This created an unprecedented opportunity for entrepreneurial people in the Duchy of Brabant. The Duke, our Lord and Master, who was also the Habsburg Emperor, stayed neutral in the conflict between the Brits and the rest. Consequently, ships sailing under that neutral flag could sail to and from the colonies. Like many others, De Wolf seized this opportunity, but as an official he had to be prudent. Again, he was helped in a mysterious way by his Chase spiritual advisors. This time their recommendation was to set up a special purpose bankruptcy remote vehicle for trade finance. That’s exactly what De Wolf did with De Wolf Solvijns (Solution).

Thanks to this SPV, De Wolf became a rich man. In 1780, the music still playing, he completely changed the nature of his business. He resigned from the civil service and set up his own bank in Antwerp, which was, in legal terms, the predecessor of the Banque de Commerce that was acquired in 1965 by Chase.

The fact that De Wolf also pulled out of the very lucrative business of trade finance must have been difficult for his fellow bankers and businessmen of the day to understand. De Wolf was convinced, however, that someday the music would stop playing and then it would be better to be out of the sector. And indeed, that’s exactly what happened.

Fortunes that had been easily made were just as easily lost, but De Wolf wasn’t affected. He concentrated on the three lines of business he intended to develop in his Bank: private banking for the upper classes, cashier services and especially public banking. It is in this latter area that big money could be made.

His largest loan ever was to the Empire of Russia (4 million guilders), but his portfolio was well diversified: France, Sweden, Prussia, Spain, the Habsburg States and the United Provinces, among others. In public banking, he consistently applied the principles of investment banking: Keep the upfront fees (4% to 10%), keep a skim on the interests, but, above all, transfer all the risks to the investors.

Life is not a fairy tale

Progressively political developments in Europe created a very challenging environment. The Brabant (1787) and the French (1789) Revolutions disrupted De Wolf’s banking model; his high-end private banking customers like the Princes de Mérode and de Ligne sought refuge in Vienna. The French revolutionaries invaded Brabant with the sacred mission to liberate and enlighten the inhabitants, even if they had to kill them first. Brabant and the rest of the Low Countries were integrated into the French Republic. De Wolf, however, didn’t like the French, and they didn’t like him. On two occasions he was taken hostage. He also suffered from health problems. Despite all that, at age 45, he married Joan Antonia Ergo (1772-1856). She was barely 20, intelligent and a remarkable beauty. She would become, in 1806, the Bank’s first and only female CEO to the present day.

Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816): the American ambassador with one leg

It is in this period that De Wolf made the acquaintance of Gouverneur Morris (image, left), the U.S. ambassador to France. As a signatory of the American Constitution, "Penman" of the Constitution's Preamble and a friend of George Washington, Morris is an historically relevant figure. For De Wolf, he proved also to be very valuable for firsthand information about the French Revolution.

It is in this period that De Wolf made the acquaintance of Gouverneur Morris (image, left), the U.S. ambassador to France. As a signatory of the American Constitution, "Penman" of the Constitution's Preamble and a friend of George Washington, Morris is an historically relevant figure. For De Wolf, he proved also to be very valuable for firsthand information about the French Revolution.

Morris lost a leg when it was crushed by a carriage. He fell under the carriage when he had to jump from the window of a lady's residence after her husband returned home earlier than expected. Morris visited De Wolf on several occasions, showing an excessive interest in Mrs. De Wolf.

Morris wore different hats: ambassador, fund raiser for the American Republic, friend to the De Wolf family, intermediary for Constable and Morris to sell real estate in Europe and others. It is in fact possible to follow the De Wolf-Morris relationship thanks to their correspondence. These letters have recently been rediscovered in New York and cover the period 1790-1810; hence unbiased firsthand information about interesting historical events lost in the fire of the Antwerp archives are preserved in New York.

Find the exotic currency?

In February 1790, two Antwerp bankers, De Wolf and Van Ertborn, reached an agreement with Morris to acquire each 200.000 Guilders of Brabant or US$130,000 in American debt, amortized over 27 years with substantial upfront fees and a skim on the interests paid (if any). Shortly thereafter, Van Ertborn was hit by the Four D’s (deviance, dysfunction, distress, and danger) and sold his loan to De Wolf considerably below par. Hence De Wolf now had a nominal US$260,000. How important was that?

In 1792 the Federal budget of the USA was about US$2.4 million with a huge deficit. So, De Wolf provided more than 10% of the total funding of the USA in one year. In comparative terms, if a bank were to take such a risk in 2019, it would be called the People’s Republic of China.

From the start, this was a very risky transaction: political risks, credit risk, transfer risks, currency risk, delivery risks. How do you get US$260,000 in gold from New York to Antwerp when the USA is still at war with a Britain that rules the waves? Undoubtedly, this transaction would be classified substandard under Chase’s credit policy guidelines from the start; heads would roll. Those crazy Belgians did it again, to put it in anachronistic terms.

As an investment banker, De Wolf’s priority was to transfer all the risks to his investors. They were reluctant to buy American bonds in USD, however; in 1790, the USD was considered an exotic currency, whereas the Guilder of Brabant was accepted all over Europe. The American bonds could not be placed directly in the market.

Certificates 1 to 200

As a true investment banker, De Wolf found a solution to the problem by creating a derivative instrument on the American bonds. He created 200 certificates with a nominal value of 1,000 Guilders, giving the subscriber the right to receive US$630 plus interest when paid. This was obviously the same risk as subscribing to the bonds directly, but a document with De Wolf’s signature did the trick to convince his investors.

Once he discovered the transforming powers of a derivative instrument, he realized that there was a possibility to hide within the certificate an option, albeit a very tricky one. But options have value especially if you get them for free. The subtlety of the certificates is that they don’t exist completely in parallel with the bonds. They are worded in such a way that the certificates pop up when the bonds are paid. They only exist at that moment. In reality, the certificate gave De Wolf the option to use the bonds for other purposes. The only thing he had to do was to keep an eye on the maturity schedule and check whether payment has been made.

De Wolf was very much aware of this possibility. He used the bonds to pay for the purchase of 440.000 acres of land in way upstate New York along the Saint Lawrence River, the present Jefferson and Lewis counties. We don’t know whether he asked for the certificate holders’ concurrence. The fact that there are still certificates popping up from time to time would seem to indicate that he didn’t.

The New York real estate transaction was clearly a mistake. For the first time in his life, he was not due diligent. He missed the three most important requirements of good real estate investments: location, location, location. The real estate was the start of an extremely complicated case that would not be solved in a satisfactory way until 1852, 46 years after De Wolf’s death–an unbelievably fascinating story, but not one for today.

Lessons learned

- Obviously, the American transaction was not De Wolf’s greatest deal. Following Chase’s procedures, it would have been a criticized asset from the beginning. During John Ward’s time as CSO Europe De Wolf would have been pressured to act. That’s what De Wolf did, he swapped an unsecured risk on the USA for 440.000 acres of land in the State of NY; except for the location of the land, this was a defendable decision.

- Capitalization of interest leads to miraculous results, especially in the long run. In 1852, De Wolf’s heirs and successors received an amount from French liquidators (connection too long to explain) in conjunction with the unpaid sale of a portion of the New York land to a French nobleman. The amount in principal was increased with 52 years of capitalized interests. Complete recovery.

- The certificate derivative was a brilliant albeit tricky piece of financial engineering–the second derivative of the initial loan–brilliant also because De Wolf transferred all risks to the investors and kept the profits. His investors didn’t lose their confidence in De Wolf. In his last will and testament, De Wolf left a sum of money to celebrate 2,000 masses for the salvation of his soul.

- From 1790 until 1798, De Wolf was the only banker willing and capable of lending to the nascent United States. He provided about 14% of the total federal budget. The question is whether this is enough to claim that it was Banque de Commerce (previously named Bank De Wolf) that laid the foundation for the USA to become a prime credit risk? In my opinion, the answer is yes.

Under Chase’s procedures such a claim would require a “one-up” concurrence. The International Center for Finance at the Yale School of Management provides such concurrent opinion. On page 295 of their book The Origins of Value: The financial innovations that created Modern Capital Markets, they represent certificate 162 of the same series as our certificate 114 and confirm that the De Wolf transaction can indeed be considered as the first step to establish the national credit of the USA. Quod erat demonstandum!

Under De Wolf the Bank was exactly the investment bank that Chase wanted us to be in the 1980s. So, except for a minor mismatch of 200 years, Banque de Commerce’s acquisition by Chase made a lot of sense.

Bibliography

Certificaet 114, Antwerpen 30 Maart 1791 (De Wolf en Deelen)

Goetzmann W. Ed., The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations That Created Modern Capital Markets (International Center for Finance at the Yale School of Management, New York 2005).

Houtman-De Smedt H., De Antwerpse Banque de Commerce 1780-1790 (Antwerpen, 1990)

Letters (150) sent by De Wolf and others in the period 1790-1810 to Gouverneur Morris et al (New York Historical Association)

Certificate 114

The owner of this document is entitled to two hundredths of the remainder of the Capital of 130,000 Dollars “Liquidated Debt”, or the liquidated debt of the United States of America, adjudicated to Jonker Charles Henry François van der Borcht, Jonker Joseph Henry de Bosschaert, and the undersigned, who have been paid on their account in the year 1790, an amount of f 200,000 change, but this right will be in force only after all the issued bonds each of f 1,000 denomination have been drawn by lot, or reimbursed, thus only of such surplus remaining after the “Liquidated Debt” might have been repaid in the meantime.

Signed: Antwerp, March 30, 1791

A.M. De Wolf

Jhr. P. Deelen

(translated by Hans van den Houten)