Life After Chase: Boudewijn Mohr

Publishes Book About Route from Wall Street

to UNICEF in Africa

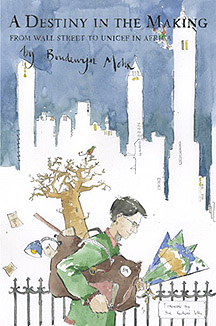

Chase Alumnus Boudewijn Mohr's new book, A Destiny in the Making: From Wall Street to UNICEF in Africa (Grosvenor House Publishing, London), is not a personal memoir as such, but covers the trajectory and transformation of a Wall Street banker towards ultimate fulfilment with UNICEF in Africa. Published in late April in hardcover, it is Amazon's #1 selling paperback in Business Travel Reference and #4 on Kindle in that category.

The Dutchman worked for Chase in Manhattan after Credit Training in London, working with French corporations in the United States.

"The book paints the extremes of my two-hatted career. It gives an insight into life in banking in the downtown Manhattan of the seventies, the patriarchal style of David Rockefeller’s Chase Manhattan Bank, sharply contrasted by a French-style banking environment of the 1980s. The other extreme was my transformation into an aid and development official of the United Nations. Once in Africa, I buried my former banker’s hat fast," Mohr writes.

While working for Chase and Société Générale, he was a columnist for a Dutch financial newspaper. As his book blurb puts it, "When the Wall Street banker takes the side of the indebted developing countries in his feature articles reviewing the impact of the global sovereign debt crisis of the 1980s in the Dutch daily NRC-Handelsblad, it is time to leave banking."

Mohr was attracted to UNICEF’s vision and goal of Health for All and its tireless pursuit of structural economic adjustment programmes with a human face. In Africa, Mohr jumped into UNICEF’s hands-on work in the field. He spearheaded the clearing of landmines in UNICEF project areas in Mozambique, and engaged with children throughout his travels on the continent. He could be found playing football with former child soldiers in Monrovia, touring Nouakchott with street children who showed him the tricks of pickpocketing or gatecrashing a diamond mine that exploits child labor near Kenema in the rebel-infested east of Sierra Leone.

"My adventurous family never hesitated to follow," Mohr said. "In fact, they started living their own adventures, in particular in sub-Saharan Africa, often working with vulnerable and marginalised children."

The book benefited from his diaries from 1985 to 2002, and surviving correspondence with his parents from 1971 to 1994. "The book tries to reach a wide audience, not in the least the younger generations in search of change and greater fulfilment for themselves and their families," Mohr said.

Part of the proceeds go to the London-based charity Hands-Up Foundation, founded by George Butler, illustrator of the book. Hands-Up supports Syrian doctors and nurses working under extremely harsh circumstances in Northern Syria.

Excerpt from Foreward by Sir Richard Jolly (leading developmental economist and former Deputy Executive Director of UNICEF):

"...At a time when it is in vogue to urge governments and non-profits to learn from

international business and banking, Boudewijn Mohr’s insightful book offers a different

lesson. It shows how much international business and the banking sector have to learn

from the UN and NGOs – about motivation and commitment, about goals focused on

human welfare rather than profit, and about broader approaches to efficiency and

effectiveness..."

Another review:

A Destiny in the Making

Tobias Denskus, Phd

Senior Lecturer, Communication for Development,

Malmö University, Sweden

June 08 2018

Even if you are only a semi-regular visitor or reader of Aidnography you have probably noticed at some point that reading and reviewing aid worker memoirs or biographies is one of my pet projects.

One of my small luxuries of being a full-time employee at a Swedish university is that I have time and space to follow this fairly impact-free small research project.

Writing about careers inside the UN system is a particularly fruitful sub-genre. Boudewijn Mohr’s A Destiny in the making: From Wall Street to UNICEF in Africa features some of the core ingredients of a good memoir as a mid-level manager reflects on almost three decades of UNICEF work starting in 1985. Mohr’s unique contribution to the genre lies in the fact that he was neither a senior executive of the organization nor did he work in particularly dangerous environments-being the country representative for Sao Tome & Principe has never been exactly a hardship post.

But Mohr’s reflections, as mundane as they sometimes must seem to an ‘in-group’ of international aid workers or -researchers, shed an interesting light on working in a bureaucratic framework under the leadership of the iconic Jim Grant. His memoir opens an interesting door to a time when UNICEF and a system of global governance expanded into a global enterprise to improve the lives of children from the perspective of someone who was close to the strategic center of the organization yet spent most of his fulfilling career a bit on the margins of global diplomacy.

From Wall Street to UNICEF-without P11, staff pools & laborious recruitment processes

Not untypical for the time, Francophile Dutch Banker Mohr has become disillusioned with the financial industry of the 1980s. Luckily under Jim Grant it was still a time ‘of the pioneers, a time of unusual management without strict rules’ (p.2) so international politics and development novice Mohr pretty much walks right into his first appointment after 17 years in banking: ‘Jim Grant signed off on an Executive Order (…) thus bypassing regular recruitment process. He did that often to speed things up or to avoid problems’ (p.25).

This is common thread in many aid worker memoirs and reminds readers of a time when international public service was run very differently-not necessarily ‘better’ or ‘worse’-and even though meetings and conferences feature heavily in Mohr’s account there is always a hint at adventure and exploration that much of the profession seem to be missing today.

My last image of Hanoi was this wrinkled old woman in a long peasant skirt speeding off on her bicycle, holding a small tree full of oranges with one hand steadily steering with the other. Such are the images of travel that stay with you forever (p.84).

I felt like I have seen this image a dozen times recently in my Facebook feed or on Instagram and many of Mohr’s vignettes on the verge of globalization and the age of ‘the Internet’ evoke a little bit of development romanticism of simpler, ‘realer’ times.

But his career is also a reminder that white or Northern men were often the beneficiaries of such informal management practices.

Establishing a global movement to save children

Mohr works at UNICEF at a time when today’s notion of global governance comes into reality: There is the Bob Geldof-inspired Sport Aid event which leads to the Race against Time in 1986, ‘the largest sporting event in history at that time’ (p.99), global summits and a growth in national committees that contribute significant funds to the organization, in short, UNICEF as a ‘brand’ emerges and has done well ever since. But Mohr’s career in Geneva or New York never seems to move into very senior leadership or management role and he even accepts to be downgraded from P5 to P4 to secure a ‘field posting’ in Africa. From a research perspective this makes Mohr’s memoir stand out as we travel with him and the family to West Africa and beyond.

Nice work if you can get it: Insights into UNICEF expat life

It is probably safe to say that for anybody who is vaguely familiar with the global aid industry Mohr’s adventures in Côte d’Ivoire, Mozambique or São Tomé & Principe are not exactly revelations. Yet, I enjoyed the final third of the book precisely for those insights into regular expat life and regular UN work in addition to global summits or photo-ops with politicians. Mohr writes in a letter to his mother in 1991: Looking back on six years in UNICEF, I feel to be in the right place. I made many friends; my work pleases me, although Saturdays and Sundays have lost their traditional meaning. These are often travel days or there is stuff to do in the office. (p.160)

As an IDS graduate I appreciated Mohr’s mentioning of Robert Chambers’ work around ‘development tourism’:

In Nairobi, I spoke with very poor children in a community school who might otherwise have been in the street. My diary explains, “I spoke with them and enjoyed it”. That, I am afraid, sounds very much like development tourism indeed. But my diary called me to order a few days later, and this is the gist of it: that I should teach and motivate – and give something back for what I have learned from them. Even this sounds hollow. (p.189).

It is his honesty and his unpretentious storytelling that turn the book into a real gem of the genre; Mohr is no ‘hero’, no UN frontline worker negotiating with fierce rebels or a smooth diplomat who charms world leaders into committing funds to children. Mohr’s career includes attending landmine workshops, advocating for a national NGO umbrella organization or setting up one of the first websites of a UNICEF country office in São Tomé.

UNICEF’s lasting impact on its staff & children around the world

I really enjoyed reading Mohr’s memoir precisely because of his insights into regular UNICEF work that keeps the organization going. Partly because of his extensive diary keeping he manages to go back to small details and daily routines within the bigger picture of UNICEF under Jim Grant’s leadership and the monumental global changes that happened at the turn of the new millennium.

A Destiny in the Making also confirms the importance of memoirs and storytelling as important avenues in writing about international development differently, personally and historically.

Mohr’s memoir is another reminder of what a powerful and lasting impression UNICEF work has made on many people-inside the organization and its impact on children around the globe.

Links To Purchase Book

A Destiny in the Making: From Wall Street

to UNICEF in Africa by Boudewijn Mohr